Why aren't humans immortal?

At first sight it would seem like a silly question, even full of pride, if taken from a strictly religious profile. Mythology itself tells us of men or demigods who dared to challenge the immortals to steal from them the gift of eternal life. Reasoning about it for just a moment, trying to grasp the purely biological aspect of the question, the thing no longer seems so absurd and meaningless; indeed, we might even regret that science is not studying with determination this wonderful topic.

Think about it carefully: if we were immortal, reproduction itself would no longer have any meaning, other than filling the Universe with our peers, as Isaac Asimov suggests to us in his famous story "The Last Question", or at least replacing individuals who died from causes other than age (let's at least try to distinguish IMMORTAL from INVULNERABLE or INDESTRUCTIBLE).

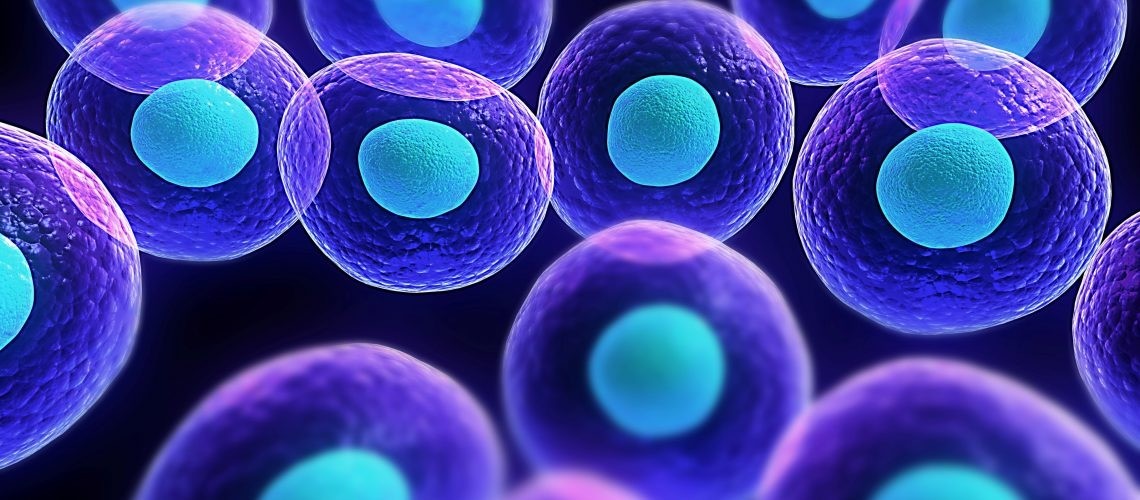

Let's get to the point: most of our cells are constantly renewed, cyclically replaced by new ones. Dandruff, for example, is nothing more than dead superficial epidermal cells, which, when pushed away, detach themselves to be replaced by a new layer immediately below.

From this simplistic perspective, each of us, as a multicellular organism, is no longer what it was a second ago, since this phenomenon occurs continuously in almost all tissues of the body, with a different turnover's rate for each cell type.

In theory, therefore, the organism is able to regenerate itself by replacing old and diseased cells with fresh, newly produced ones. Yet none of us, as the years pass, lose our identity. We all retain the memory of ourselves as we were years before, albeit aware of having grown up and aged a little. None of us would deny the multicellular agglomeration that was previously there, no longer recognizing itself due to cellular renewal!

Beyond this witty observation, we must keep in mind that this replacement can also only occur at a molecular level, that is, in the individual bricks that make up the cells. Just think of nerve cells: as complicated as they are, with their intricate ramifications that make up nerve fibers, how could they ever divide, like an enviable protozoan? In reality exists a phenomenon of partial regeneration, but since these are particular cases, I would prefer to gloss over it so as not to go into too much futile detail. What matters is that the turnover is there, it is not an utopia. It exists, it happens, and looking at it like this we may even seem to be a few steps away from immortality... Yet, despite this apparent perfection, in reality organisms age and fatally die, being replaced by new generations to thus perpetuate indefinitely (evolution permitting) their genetic identity, that apparently stable biological concept that we call SPECIES.

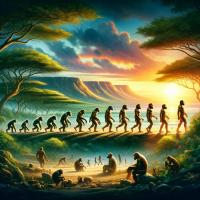

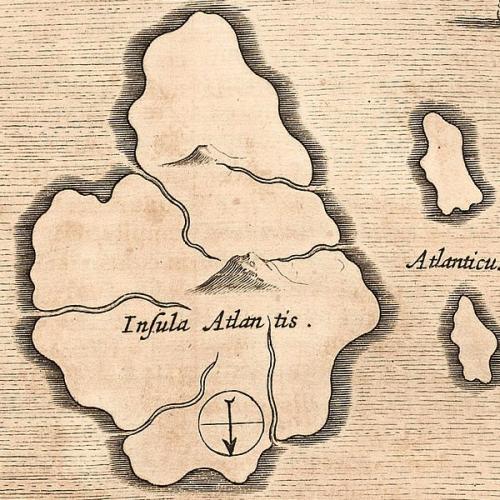

What does all this mean? Why in hundreds of millions of years of speciation, of refinement of organisms, from the primitive multicellular Mesozoans to today's complex Vertebrates, hasn't the mechanism of cellular renewal and replacement also been perfected, to the point of reaching perfect global replacement, and therefore immortality? What can science, the genetic engineering of the future, do to guide human evolution in this direction apparently ignored by Mother Nature?

At this point the discussion becomes a bit complicated: it would be necessary to explain at a molecular level what happens to cells and tissues when they age, what happens to the telomeres of chromosomes which shorten over time, the oxidative processes of free radicals, the mechanism of repair of DNA mutations and so on, that is, because the colony, the perfect machine that is each of us, at a certain point, or rather gradually, no longer "holds" itself, falls apart, therefore ages, leading us inexorably to death.

It may be interesting (although I would necessarily have to go into overly scientific explanations), but it does not resolve our original question: why then are we not immortal? The answer is: we are not immortal because we get older.

We may also be able to explain exactly what happens in the tissues and individual cells of the organism, even finding in a not too distant future (molecular biology is making giant strides) a solution to slow down, even stop this phenomenon (a modern version of the potion of eternal youth), but this would not explain at all (even if it would bring happiness to the human race!) the primary cause, the one that lies upstream, that is: what is behind all this? Why is a bacterium eternal in its "simple" duplication, and we are not?

The more astute of you will have already identified the answer, but I want to explain.

Probably the meaning of life lies precisely between these lines: there is really no reason to rejoice about it, absolutely none... on the contrary.

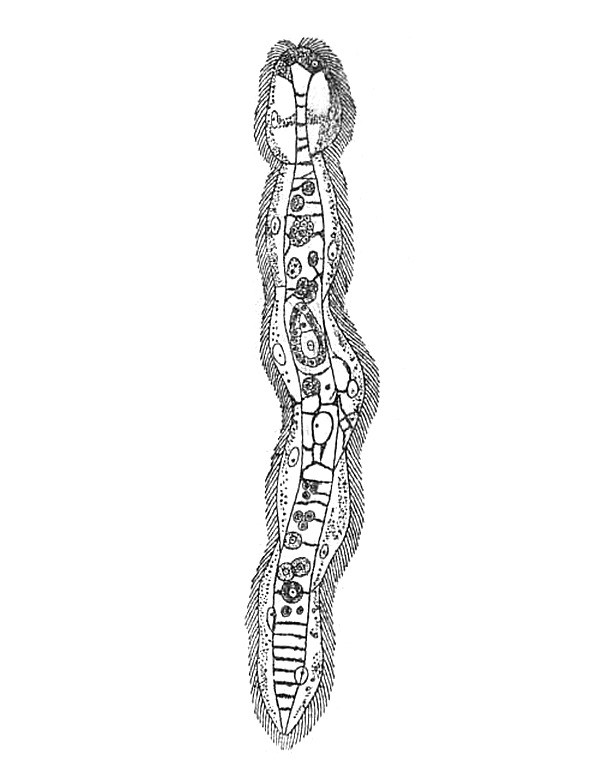

First of all, we are multicellular, and this is our condemnation. I therefore insist that we are nothing more than walking colonies like plants, corals, ...

We are colonies of cells that collaborate closely, specialized in a division of tasks pushed to the point of excess (just think of nerve, bone and liver cells) in order to obtain a clear improvement and evolutionary advantage in the eternal fight against adversity. Yet this "improvement" often involves tragic sacrifices. A few significant examples: a nucleated red blood cells, haploid gametes, keratinized epithelia, calcified osteocytes. Faced with such a cruel, even atrocious cellular destiny, how could we not envy the erratic and autonomous existence of a flagellated protozoan?

Summing up therefore, the fate of the single specialized cell is of no interest to anyone, but rather it is the complex that counts - the usual cruel, ruthless natural selection on evolution by random mutation - and unfortunately, even if reluctantly, we are forced to admit that all in all we are better off than a small single-celled bacterium, at least in the fight against the hostile environment. But who are we?

We feel like living units in our own right, individual organisms, but that's not true. We make single what is plural while, as colonies, when we express ourselves in the first person, perhaps we even do something that has no meaning. But here we are entering directly into philosophical-existential delirium, colliding once again with the evanescent meaning of life, which perhaps never existed.

So, what do we have in common with a "luckier" bacterium? Simple: REPRODUCTION. That's the sad answer. From the beginning, for over four billion years, the molecular mechanism of life has been replication, making use of nucleic acids: in the beginning RNA (some viruses still use it as a genetic code), and then DNA. It therefore little matters if over time some cells of a multicellular organism are no longer capable of reproducing (as a bacterium does continuously) and are subject to degeneration and death. The important thing is that the colony "holds on" as long as possible, just long enough to allow the individual to mate, multiply and therefore the species (i.e. that specific DNA molecule of which we macroorganisms are only the phenotypic reflection) to to preserve itself... or better yet to renew itself, transform itself, thanks to mutations, into new evolutionary challenges always in step with the changing environment. At this point, the colony-individual has fulfilled its duty: it has propagated by generating a more or less faithful copy of itself, which is thus entrusted to the severe and impartial judgment of natural selection. So what matters more than the fate of the old parent? What evolutionary pressure could possibly favor a useless and certainly harmful immortality?

That it is useless can be seen clearly in the basic mechanism which is Reproduction / Replication: the lifespan of every organism has a duration more than sufficient to fulfill this duty, the only true meaning of the existence of the nucleic acids of which we macroorganisms are the very complicated expression of this. As for the harmfulness, try to imagine how the Earth would be a little overcrowded if no living being had ever died from four and a half billion years ago to today! Apart from this absurdity (such for a lot of reasons) there is then the qualitative and functional aspect, less evident but more important, which has allowed such a harmful phenomenon as genetic mutations to instead become the fundamental prerequisite thanks to the which on this planet there is still life, distributed in many different forms (and let's not forget the extinct ones) in every corner of the globe to cope with the instability and mutability of environmental conditions (and I don't just mean climatic, but geological, ecological, chemical-physical and astronomical), to which Life has responded since the beginning in the only way in which it was capable and which allowed it to remain so tenaciously clinging to the planet despite its most terrible catastrophes: by changing. And how can we change, if not from generation to generation, drastically rejecting the immortality of individual eternal and perfectly static organisms, incapable of opposing environmental changes? Or on the contrary: how could reproduction have been forcefully imposed if it no longer had a purpose in a world of immortal beings?

A minimal fluctuation in environmental stability would have been enough to erase Life from the planet, probably a single immortal species, definitively. And if this already happened billions of years ago, during the phase of massive asteroid bombardment that repeatedly wiped out life from the Earth, we will probably never know.

ALWAYS RENEW YOURSELF, this therefore has been, is and will be, until the sunset of Life, the motto of all living organisms, prokaryotes or sexual eukaryotes; whoever stops is condemned, since - I repeat myself again at the risk of sounding monotonous - they would quickly lose pace with continuous evolution in an equally changing environment,

where there would be no place for anything absolutely static (genomically speaking). At this point someone might observe indignantly: but couldn't the individual already alive and therefore in more direct contact with the fluctuating environment adapt, rather than his offspring relying on blind and often deleterious random mutations?

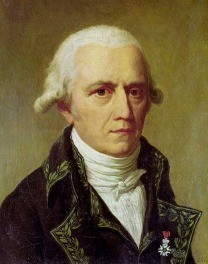

Certainly; so in fact a certain G. B. Lamarck asserted, in his "Zoological Philosophy"; the French erected a monument to him, but then, if I'm not mistaken, it appears to me that it was the good C. Darwin who ultimately prevailed over every other theory, therefore, until proven otherwise or whether religious anathema, it is advisable to declare ourselves his avid followers. And with this I concluded.

So this is what Life is. This is our miserable context as self-conscious creatures in the cruel ocean of molecular existence. A twist of fate? What is the point of having reached this "evolutionary goal" of intelligence, only to then discover that we are being kicked by a game as old as the world, from which we would like to escape only in the name of our intellectual superiority, while instead we are an integral part of it until to the last atom, no more and no less than a mushroom, a sponge, a poppy or a leech? Here we are: clumsy and ridiculous wandering structures, tormented by the weight of the awareness of being nothing other than what we are.

Isn't this what we have called "Evil" for centuries? On the one hand, scientific investigation, digging ever deeper into the micro and macroscopic, leads us towards mass suicide, on the other, religions lull us into evanescent illusions. I leave the choice up to you. As for being immortal, well, it is Nature itself that answers us: WHAT FOR? (And don't tell me you were all disappointed!)