Copy Link

Add to Bookmark

Report

Public-Access Computer Systems Review Volume 03 Number 08

+ Page 1 +

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review

Volume 3, Number 8 (1992) ISSN 1048-6542

-----------------------------------------------------------------

To retrieve an article file as an e-mail message, send the GET

command given after the article information to LISTSERV@UHUPVM1

(BITNET) or LISTSERV@UHUPVM1.UH.EDU (Internet). To retrieve the

article as a file, omit "F=MAIL" from the end of the GET command.

CONTENTS

COMMUNICATIONS

The New Publishing: Technology's Impact on the Publishing

Industry Over the Next Decade

By Gregory J. E. Rawlins (pp. 5-63)

To retrieve these files: GET RAWLINS1 PRV3N8 F=MAIL

GET RAWLINS2 PRV3N8 F=MAIL

This report discusses technology's impact on the products,

revenue sources, and distribution channels of the publishing

industry over the next decade. It examines the threats and

opportunities facing the book publishing industry, and presents a

strategy for publishers to meet the threats and to use the

opportunities to decrease risk and increase profit. The strategy

also benefits education, science, and technology by making books

cheaper, more flexible, and more easily and quickly available.

1.0 Overview

1.1 Electronic Books and Copy Protection

1.2 Subscription Publishers

2.0 Threats to Contemporary Publishing

2.1 Paper Copying

2.2 Electronic Copying

2.3 The Future of Copyright

3.0 Electronic Book Advantages

3.1 Reader Advantages

3.2 Library Advantages

3.3 Publisher Advantages

+ Page 2 +

4.0 Retailing Schemes

4.1 Disc Bookstores

4.2 Electronic Bookstores

4.3 On-Demand Bookstores

4.4 Locked-Disc Publishers

4.5 The Future of Retail Books

5.0 Changes in Education

5.1 Electronic Science Books

5.2 Other Educational Books

5.3 The Frailties of Print

6.0 The New Publishing

6.1 Mapmakers, Ferrets, and Filters

6.2 Stage I Penetration

6.3 Stage II Penetration

6.4 Stage III Penetration

7.0 Gearing Up

7.1 A New View of Economics

7.2 Why It Will Work

7.3 A New View of Publishing

8.0 Getting There From Here

8.1 The Short Term

8.2 The Mid Term

8.3 The Long Term

9.0 Pricing, Positioning, and Profits

9.1 Lures to Subscribe

9.2 Global Publishers

9.3 Competition

9.4 Entrepreneurs

10.0 Technological Hammers

Appendix A. Electronic Book Technology

Appendix B. Electronic Book Players

+ Page 3 +

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review

Editor-in-Chief

Charles W. Bailey, Jr.

University Libraries

University of Houston

Houston, TX 77204-2091

(713) 743-9804

LIB3@UHUPVM1 (BITNET) or LIB3@UHUPVM1.UH.EDU (Internet)

Associate Editors

Columns: Leslie Pearse, OCLC

Communications: Dana Rooks, University of Houston

Reviews: Roy Tennant, University of California, Berkeley

Editorial Board

Ralph Alberico, University of Texas, Austin

George H. Brett II, Clearinghouse for Networked Information

Discovery and Retrieval

Steve Cisler, Apple

Walt Crawford, Research Libraries Group

Lorcan Dempsey, University of Bath

Nancy Evans, Pennsylvania State University, Ogontz

Charles Hildreth, University of Washington

Ronald Larsen, University of Maryland

Clifford Lynch, Division of Library Automation,

University of California

David R. McDonald, Tufts University

R. Bruce Miller, University of California, San Diego

Paul Evan Peters, Coalition for Networked Information

Mike Ridley, University of Waterloo

Peggy Seiden, Skidmore College

Peter Stone, University of Sussex

John E. Ulmschneider, North Carolina State University

Publication Information

Published on an irregular basis by the University Libraries,

University of Houston. Technical support is provided by the

Information Technology Division, University of Houston.

Circulation: 5,090 subscribers in 47 countries (PACS-L) and 770

subscribers in 37 countries (PACS-P).

+ Page 4 +

Back issues are available from LISTSERV@UHUPVM1 (BITNET) or

LISTSERV@UHUPVM1.UH.EDU (Internet). To obtain a list of all

available files, send the following e-mail message to the

LISTSERV: INDEX PACS-L. The name of each issue's table of

contents file begins with the word "CONTENTS."

-----------------------------------------------------------------

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is an electronic

journal that is distributed on BITNET, Internet, and other

computer networks. There is no subscription fee.

To subscribe, send an e-mail message to LISTSERV@UHUPVM1

(BITNET) or LISTSERV@UHUPVM1.UH.EDU (Internet) that says:

SUBSCRIBE PACS-P First Name Last Name. PACS-P subscribers also

receive two electronic newsletters: Current Cites and Public-

Access Computer Systems News.

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is Copyright (C)

1992 by the University Libraries, University of Houston. All

Rights Reserved.

Copying is permitted for noncommercial use by academic

computer centers, computer conferences, individual scholars, and

libraries. Libraries are authorized to add the journal to their

collection, in electronic or printed form, at no charge. This

message must appear on all copied material. All commercial use

requires permission.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

+ Page 5 +

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Rawlins, Gregory J. E. "The New Publishing: Technology's Impact

on the Publishing Industry Over the Next Decade." The Public-

Access Computer Systems Review 3, no. 8 (1992): 5-63. To

retrieve this article, send the following two e-mail messages to

LISTSERV@UHUPVM1 or LISTSERV@UHUPVM1.UH.EDU: GET RAWLINS1 PRV3N8

F=MAIL and GET RAWLINS2 PRV3N8 F=MAIL.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Abstract

This report discusses technology's impact on the products,

revenue sources, and distribution channels of the publishing

industry over the next decade. It examines the threats and

opportunities facing the book publishing industry, and presents a

strategy for publishers to meet the threats and to use the

opportunities to decrease risk and increase profit. The strategy

also benefits education, science, and technology by making books

cheaper, more flexible, and more easily and quickly available.

1.0 Overview

You can count how many seeds are in the apple, but not how

many apples are in the seed. Ken Kesey.

Over the past two decades printing, paper, and transportation

costs rose while their electronic counterparts--computing,

electronic storage, and communication costs--halved roughly every

four years. Both trends are expected to continue for at least

two more decades. [1]

The last time something this radical happened was in the

15th century when the printing press used the newly available

cheap paper to take over the manuscript market, throw scribes out

of work, and explosively increase the number of available books.

Print led to pagination, indices, and bibliographies since

they were now possible and they made searching easier. And that

forced people to learn the alphabet so that they could use the

new indices. Print increased literacy, democratized knowledge,

increased accuracy, made fiction possible, made propaganda

possible, created public libraries, and created the idea of

authorship.

Print also decreased the importance of memories--and their

main possessors, the elders; loosened the hold of the Church and

led to the Reformation; added fuel to the Humanist movement and

led to the Renaissance by putting classical authors back in

print; increased education, science, and technology transfer; and

created publishers.

Electronic books may bring changes of similar magnitude.

+ Page 6 +

1.1 Electronic Books and Copy Protection

Today we can scan a printed book into electronic form, then

distribute it over the phone in minutes to hundreds of people at

pennies a copy. Further, we can produce books electronically

without ever committing them to paper. Finally, we can augment

electronic books to include sound, motion pictures, and automatic

cross-referencing. Electronic books can be easier to distribute,

less expensive, less risky, more powerful, more flexible, more

immediate, and easier to search and collate. They can also be

interactive, changeable, and adaptive.

For these reasons, and others detailed in this report,

electronic books will become a large part of the book market

within the decade. And that will make it harder for publishers

to ensure that their increasingly expensive books are not

illegally copied.

Traditionally, publishers and authors have used copyright

and the courts to protect their investment. So the natural way

for publishers to adapt to the new technology is to copy protect

their books, as software publishers and video producers first

tried, and recording artists are still trying, to protect their

products. Copy protection is like putting a lock on each copy

then selling a key with each locked book.

Protections on marketable intellectual properties try to

equate intellectual properties, like this report, with tangible

properties, like ham sandwiches, or rights on tangible

properties, like franchises, licenses, water rights, stock

futures, or airline routes. Because of their artificiality, it

could be said that copy protection merely feeds lawyers and

annoys legitimate users. Whether that position is defensible,

copy protection certainly adds expense and works against easy

searching and collating. So for educators, scientists, and

technologists it would be desirable to avoid it, if possible.

The information in books is freely accessible; this ease of

information exchange makes civilization go. But paper books are

not easy to search, cross-reference, index, collate by multiple

subjects, or carry in bulk. It will increase information

distribution, and benefit education, science, and technology, if

there was some way for publishers to make their books cheap,

electronic, and not copy protected. That would keep the freedom

of paper while increasing searchability and availability.

+ Page 7 +

1.2 Subscription Publishers

Publishers can accomplish all the above aims by becoming

subscription services, charging subscribers a small monthly fee

for the ability to get any of their books electronically over the

phone, at a small cost per book. Among other business advantages

detailed later in this report, such publishers are immune from

pirates.

These publishers can also benefit education and science.

Further, they may speed up technology transfer from the research

lab to the factory floor. Both education and science flourish

when information is easily and widely available, and easy to

distribute, compare, refine, search, and collate. The

subscription scheme can make marketable information cheap, easily

available electronically, and easily translatable from one

electronic medium to another.

And publishing will cost less, so more people can become

publishers, thereby increasing title diversity. More diversity

seems necessary when 2 percent of all publishers produce about 75

percent of all U.S. book titles and when the three largest

bookstore chains generate about 40 percent of all retail

bookstore revenue. [2] The U.S. now has about 6,500 independent

bookstores and the top three chains own about 2,750 outlets.

More publishers would increase title diversity leaving the

market to decide which are good--as is true on the electronic

network, but not in print. When everything is committed to paper

the few can control what the many can read by controlling the

bottleneck--the printer. That is like letting Kodak control the

movie industry since it produces the most film.

The electronic network is the equivalent of the road system

today. Instead of killing trees, printing books, loading a

truck, train, plane, or ship with crates of books, expending oil

and human labor to transport them to various retailers, polluting

the environment, and taking days to do so, any book can be sent

on demand directly from the publisher to any reader in the world

in seconds. This is also true for any other information--movies,

software, music, television shows, or radio shows.

Books can be more easily distributed if they were

electronic, and publishers can profit without copy protecting

their books. The scheme makes books cheaper both to publishers

and to readers, reduces the risks of publishing, and increases

publisher profit. It works by shifting the publishing emphasis

from betting that one particular title will be a bestseller to

maintaining many readers of at least one title.

+ Page 8 +

In a decade, publishers will be back to doing what they do

today. Once the novelty of electronic books wears off,

publishers will again compete to ensure that their product is

better designed, better packaged, and better promoted than that

of their competitors. But because of the coming economic

dislocation, in the intervening decade unprepared publishers may

fail.

This report examines the threats to contemporary publishing,

describes the advantages that are forcing it into existence, and

presents a way for publishers to succeed in the new publishing.

It concentrates on possible electronic formats, revenue sources,

and distribution channels of the publishing industry. And it

briefly mentions changes in the publishing process itself, and

governmental, geopolitical, economic, legal, and social changes

brought on by the new milieu. It is biased toward the interests

of scientists, technologists, and educators.

2.0 Threats to Contemporary Publishing

The race is not always to the swift, nor the battle to the

strong, but that's the way to bet. Damon Runyon.

Because of the costs of paper publishing and publisher

assumptions about how to make books return a profit, a 500-page

textbook typically costs $50 retail, or 10 cents a page. Second-

hand it costs $25, or 5 cents a page. On a large copier it costs

$15, or 3 cents a page. On a large printer it costs $5, or 1

cent a page. If it were distributed electronically, it would

cost about $1 to send it to any phone in the world, at a cost of

1/5 cent a page. And whether it is an excellent or a terrible

book does not change these cost differences.

2.1 Paper Copying

The short-term threat is that fast high-resolution color copying

technology is now so cheap that enforceable copyright is becoming

a thing of the past. Publishers will not face threats from large

copy stores because they are a large enough target that they can

be sued, but now individuals can afford personal copiers. For

example, the Canon PC-311 costs $400. And this is not an

industry that is about to disappear; worldwide, the copying

industry now sells $14 billion worth of equipment, of which Canon

alone accounts for $3.5 billion. [3]

+ Page 9 +

Worse, copiers are going to get smaller and cheaper.

Electronic storage costs have dropped so low versus printing

costs that a copier can be merely a scanner with a capacious

memory. Such a copier could be palm-sized--it would be

attachable to a separate computer or printer. Because electronic

storage is now so cheap, it is no longer necessary to print pages

when the original is scanned.

Over the past two decades the cost of a short ton of

newsprint has gone from $150 to $550. It is not that paper has

become an insupportably expensive medium overnight, but

electronic storage cost has plummeted so much that paper's cost

has skyrocketed.

Imagine a world of small cheap personal copiers, where you

can rent, then copy, expensive paper books just as you can rent

music, software, or movies today. Imagine a world where one

student in a class buys a copy of a textbook, then copies it for

all the others. Imagine a world where publishers in Pacific Rim

and Middle Eastern countries buy one copy of a book then sell

duplicates just above the duplicating cost.

2.2 Electronic Copying

The copying problem will grow even worse as books become

electronic because copying electronic information is easier than

paper copying, and it can be done without human labor. Once

books are electronic then at some point the book must be decoded

for the user to read. At this point it can be copied.

Perfectly. Further, this copy's cost, being equivalent to the

cost of the storage needed to hold the copy, is effectively zero.

Finally, once a copy is made, both copies can be used at the same

time; where there was once one copy there are now two separate

and perfect copies.

Even if publishers try to avoid electronic copying by

staying with paper, readers could scan their paper books into

electronic form.

There are ways to copy protect electronic media in the short

term (a year or so at a time), but they are soon broken by

pirates. So there is an escalating copy protection cost.

Further, copy protection is odious to some and may not gain wide

acceptance for something as fundamental as a book. Finally, if

books continue to cost more than it costs to copy them, then

publishers and authors will always lose money to pirates.

+ Page 10 +

Authors and publishers use copyright to protect their

investment of time, creativity, and capital, but that protection

is eroding rapidly. There is no long-term copy protection scheme

suitable for marketable electronic books; the user can always

scan the book and copy it perfectly. It will merely take longer

to make the first copy.

Some publishers may price their books so high that they will

profit even if only a few copies are sold. Today, some

publishers charge libraries high prices on the principle that

many people use a book at a library. But if publishers try

either copy protection or high prices, or copy protection to

enforce high prices, a breed of intellectual terrorists may

arise, who will break their copy protection and anonymously

distribute unprotected copies for free along the electronic

networks (for example, see the NuPrometheus league discussed in

Branscomb). [4] And millions of people are reachable

electronically. Of course, such a market also encourages

pirates.

The problems facing the publishing industry seem

insurmountable, if publishing proceeds as it does today except

that books are electronic instead of on paper. But with a new

view of publishing the apparently severe problems become

opportunities. The only viable long-term solution is for

publishers to make book buying cheaper or more convenient than

book copying, as it used to be five years ago. Publishers can do

so if they keep a stable number of captive readers and amortize

costs over their entire list.

2.3 The Future of Copyright

As happened in the music industry, the software industry, the

television industry, and the movie industry, publishers will have

to adapt to the new technology. Like every other business, it is

natural for publishers to want to continue to operate as they

have done in the past. But they may not be able to. Once a few

publishers take advantage of the technology, other publishers may

be forced to comply. As has happened in the most staid of all

industries--banking.

In 1977, Citibank's share of retail deposits was 4.7

percent. Citibank realized that it could increase market share

by reducing its unit costs; revenues would increase if it could

attract many more low-balance customers. Citibank invested at

least $250 million to deploy roughly 500 automatic teller

machines (ATMs). By 1982, it had more than doubled its market

share, and its share continued to rise by about 1 percent a year

since 1983. By 1990, its share of the retail market was 14.7

percent--triple its 1977 share. [5]

+ Page 11 +

In 1983, eight other banks banded together to meet the

threat and formed NYCE (New York Cash Exchange). By 1988, NYCE

was the second largest shared ATM network in the world, trailing

only France's Carte Bleue. Today it alone provides instant 24-

hour service to over 11 million cardholders, who can use over

6,000 ATMs owned by 360 banks in 22 states. Many new bank

branches are merely a series of ATMs set into a wall, with no

tellers at all. Today a bank's ATM network is not a competitive

advantage, it is an economic necessity.

Information is not the same as tangible goods; it can be

copied almost instantly over enormous distances, with no trace,

no loss in fidelity, and, potentially, no loss in value. This is

true for pictures, designs, music, movies, software, and books.

In the information economy, the ability to read something is

inextricably bound up with the ability to copy it. When a few

million people have the means of duplication in their hands

copyright may exist as an idea, but it will be unenforceable

between publishers and the public. Today no one is arrested for

making personal copies of audiotapes or videotapes, even though

that principle has never been tested in court. [6] We could

control illegal drugs easily if they had to enter the country

through a few large depots.

But avoiding copy protection does not mean giving up

copyright, particularly since the new technology allows abuses of

copyright between authors and publishers and between publishers

and retailers. That was not possible when production and

distribution were so expensive that they were solely in the hands

of publishers, and publishers had to be large companies just to

be publishers. In those days, authors could always sue their

publishers, and authors could not cheaply distribute their own

works. But now that production and distribution are affordable

by individuals, and growing ever cheaper, cases will eventually

arise of publishers hiding sales from their authors, of retailers

hiding sales from their publishers, of publishers selling

independent of their retailers, and of authors selling

independent of their publishers.

However, the subscription scheme is immune from attack

because it makes book buying cheaper and more convenient than

book copying. To see why it can work, imagine that someone

invents a programmable matter transformer that can produce food

from sand. Now imagine that the technology is so cheap that

everyone can own one. It would then be foolish to try to sell

food. But you can still sell recipes. And the same would be

true of pharmaceuticals, jet engines, or microprocessors, only

the producers and consumers change.

+ Page 12 +

What will make consumers come back for more? The promise of

more delicious recipes. The next section discusses what will

make those recipes delicious.

3.0 Electronic Book Advantages

To describe the evolutions in the dance of the gods . . .

without visual models would be labor spent in vain. Plato,

The Timaeus.

The advantages of printed books as a medium of information

storage and exchange are that they are robust, they need zero

power, several can be open at once, they have been around for 550

years, all literate people know how to use them, and they are

readable in strong sunlight.

Their disadvantages are that illiterate people cannot use

them, it is easier to print an electronic book than it is to

digitize a printed book, and it is hard to collate non-sequential

but related parts of one book, or many books by several subjects.

Further, they do not talk, adapt to their readers, or have

animated illustrations or music. They do not let readers zoom or

pan illustrations, or increase or decrease their font size, nor

do they recognize voice commands or visual cues. Finally, they

are not cheap, long lasting, easily copied, quickly acquired,

easily searched, or portable in bulk.

Paper will be with us for decades to come because of the

hundreds of years of technological development behind simple,

cheap, light, detachable pieces of paper, and the complementary

use of hand and eye to arrange, read, or write them. It will be

many decades before another piece of technology called virtual

reality (not discussed in this report) eclipses paper. But

because of their advantages to readers, libraries, educators,

publishers, and retailers, in a decade electronic books will be a

significant part of the market. About all that can be said of

paper books is that they are lighter than clay tablets, less

awkward than papyrus rolls, and cheaper than parchment codices.

+ Page 13 +

3.1 Reader Advantages

When books are electronic, readers can have instant and

unsleeping access, as in banking. Also, readers can have instant

updates and revisions, and electronic contact with all other

readers of each book, thereby sharing ideas and reactions more

rapidly and with more people. For publishers this means that

word of mouth can sell more books more quickly. Further,

electronic books need not go out of print. And electronic books

are cheaper and less bulky than paper books. Instead of several

expensive books, where although each one is portable, large

numbers are not, thousands of books can be stored on one small

light disc, at 8 cents a book.

Making books electronic makes them computer readable, so

books can contain electronic bookmarks and cross-referencing.

Cross-referencing can be either reader controlled or computer

generated. And all the advantages of paper books--handwritten

annotation, highlighting with colored markers, underlining, post-

it notes, bookmarks--can be allowed through software on small

portable pen-based computers (for example, see Phillips). [7]

Also, books can be customizable by, or for, their readers; a

copy of a book need no longer be an exact copy--as has already

happened in consumer-targeted advertising. Because the

information economy is computer-based and global, with

concomitant increased knowledge of consumer tastes and increased

competition, it will become increasingly lifestyle-targeted.

Unlike paper books, electronic books can be multimedia:

letting us mix voice, music, color, motion pictures, data, and

text, and leading to animated talking books. For example, the

Xerox/Kurzweil Personal Reader can read the text of any book out

loud--an invaluable aid to the blind, sight-impaired, illiterate,

or busy--it is unnecessary to first record an actor reading the

book. [8] The Personal Reader trains itself on any printed text

and gets better as it progresses down the first page. It can

read six languages.

A program called NETtalk [9] can be used to produce a

children's book that is really a whole library of children's

books. The book listens to the child (or parent) reading aloud

for a few hours until it can read any of its repertoire of books

in that voice.

Imagine children's books that read themselves to a child at

bedtime. By listening to the child's breathing, the book can

reduce its volume, dim the lights, and slow its cadence as the

child drops off to sleep. This can be done today.

+ Page 14 +

3.2 Library Advantages

Electronic books mean that libraries need not keep large and

expensive stores of bulky and decaying paper. Libraries can

shrink from large warehouses to small rooms. And catalogs can be

electronic, electronically updatable, and computer generatable,

making them easier, faster, and cheaper to search, produce, and

update. Libraries will not need to buy multiple copies to allow

for book scuffing or book destruction. Nor will they need

binderies to bind journals or magazines into volumes, or to

rebind old books. Nor will they need shelvers. Also, the

library can more easily refer readers to other books with similar

subjects, tastes, or interests.

Libraries will not need to chemically treat their decaying

books, microfilm them, or transcribe them to Braille, large-

print, or audio. All transformations are easier with electronic

books. Currently, the Library of Congress can afford to

transcribe only 2,000 new books and 1,000 new periodicals a year.

Out of its 20 million books, it carries only 30,000 in alternate

formats.

3.3 Publisher Advantages

Contemporary publishing is risky business. Because of the

economics of paper printing and distribution, titles have to be

produced in large print runs to make it profitable to sell them.

But there is no guarantee that a book will sell its print run.

Large print runs mean that much capital is tied up in

product for a long time. So less capital is available to buy new

titles or to promote current ones. It further means large

transportation, warehousing, security, insurance, and

distribution costs. And all the people who do this have to be

paid salaries, workers compensation, and pensions.

But small print runs mean risking running out of stock and

losing customers to competing titles because of delay. Further,

because printing costs drop sharply with volume, many small print

runs are unprofitable.

Even if demand could be predicted exactly and even if titles

could reach readers as soon as they are printed, printing alone

adds four to six weeks to product delivery. And unless product

is mailed express at greater cost, the post office adds a further

two to three weeks. Finally, even if warehousing and capital

costs are zero, product cannot be kept awaiting demand

indefinitely since it is bulky and it physically decays in a few

years.

+ Page 15 +

Because of these constraints imposed by committing books to

a fixed medium (here paper, but similar things would be true of

discs), publishing proceeds by guess and by gosh.

Publishers let retailers return unsold copies to increase

the chance that retailers can afford to carry their titles.

Sometimes as much as half of a mass-market fiction print run of

500,000 copies is returned. But with electronic distribution,

outlets will not have to keep as many copies of each title as

they think they can sell; they need only one for promotional use.

And that will increase the diversity of titles outlets can offer.

Eventually, distribution costs to publishers could drop to zero

since readers could acquire product rather than publishers

supplying it.

Further, when distribution is electronic, used-textbook

stores go out of business. Currently, a textbook may sell 10,000

copies in the first year, 5,000 copies in the second year, then

2,000 in the third year. The original 10,000 market is still

there, but it is being serviced by used copies. The used

bookstores are piggybacking on the publisher's and author's

investment of time, capital, and creativity. Electronic

distribution eliminates that opportunity since the most recent

version can be available instantly and cheaply.

Going to electronic books and electronic distribution of

them on demand means no printing and its costly consequences:

warehousing, transportation, delay, back-ordering; competing for

scarce outlet shelf space; overestimating demand and having to

remainder or destroy books; underestimating demand and having to

lose business or annoy customers; and sinking large amounts of

capital into paper copies that take time to sell, that take up

shelf space, that decay on the shelf, that may be returned after

sale, and that if sold then fuel the used book market.

Production would become editing, reviewing, and developing

acceptable projects. Printing and distribution will cost little.

And there will be more resources available for acquisition and

marketing. Finally, in the subscription scheme publishers will

have large stable incomes over a period of years, thereby making

it easier to attract venture capital for start up or expansion,

making planning easier, and reducing risk.

+ Page 16 +

4.0 Retailing Schemes

First secure an independent income and then practice virtue.

Greek proverb.

Today, retailers must risk almost as much as publishers. Most

bookstores carry anywhere from 1 to 1,000 copies of each title,

depending on expected demand. All but one are redundant.

Electronic media let retailers choose a melange of distribution

schemes to reduce risk and increase profit.

4.1 Disc Bookstores

From a standing start in 1984, compact discs overtook phonograph

records in five years. Paper books will put up more of a fight

because of inertia and because it will take time for adequate

display technology to reach many people. But it is inevitable.

In seven years, some bookstores will become half compact

disc stores, thereby quadrupling the number of titles per meter

of shelf space, but otherwise keeping many of the ills of paper

publishing since retailers will still have to order as many

copies of each title as they think they can sell.

This will take seven years or more to allow for the time

needed to scan most of the books that exist only on paper and to

allow for cultural inertia and technophobia; some people will

dislike the idea of electronic books. But once a book exists in

at least one electronic form, it is easy to print it if

necessary, convert it to another electronic form, or distribute

it electronically. Electronic books contain paper books as a

special case.

4.2 Electronic Bookstores

In seven to ten years, some bookstores will disappear into the

woodwork. These bookstores may become just wall-sized display

screens electronically displaying an array of titles, with

pictures. Each title may be in its own book-sized rectangle of

the display. Customers could use their electronic pens to wand

the appropriate title(s) and have it automatically delivered to

their portable or home computer and their credit card

automatically charged. To allow browsing, perhaps a part of the

book is downloaded to the portable first (reviews, description,

sample pages, and a list of previous books written), and the sale

goes through if the customer does not discard the preview after

half an hour.

+ Page 17 +

Major book chains like Waldenbooks, B. Dalton

Booksellers/Barnes & Noble, Crown, Coles, Waterstones, and W. H.

Smith's would love such a system. They would love it so much

that they may become publishers themselves. They would have

little space to rent, no staff salaries, no stock, no

warehousing, no transportation, no remainders, no returns, no

overhead, no need to reshelve books, no need to discard scuffed

books, and no need to insure against fire, theft, or water

damage. Further, it is easy to reorganize the display, and the

display operates continuously.

These bookstores are interactive billboards. Retailers

could put them anywhere people congregate (bus stops, church

yards, and playgrounds) and even on vehicles (buses, trains,

planes, and ships).

When books are electronically distributed, a publisher (or

retailer) can produce catalogs that are really databases with a

front-end program to help customers query the catalog. The top

level display might be a menu of all the subjects the publisher

(or retailer) groups their books by. Customers move through the

catalog searching for books they want, and can immediately

receive them (and pay for them).

Such a catalog would also be cheaper than print. A typical

64-page print catalog destroys trees and costs over $2 per

catalog, a disc version for several apparel companies costs $1.28

per disc, including production and mailing. [10]

The catalog can instantly reflect demand for each title.

The Italian apparel company Benetton uses its worldwide system to

determine the demand for each fabric, and what color it should be

dyed for the next week's fashions. Benetton has drastically

reduced both inventory and lost sales. The publisher (or

licensed retailer) can print some fraction of the demand for each

title to service the paper trade. The electronic service acts as

a market sample, giving a more accurate estimate of demand than

today's print run system.

4.3 On-Demand Bookstores

Electronic books are more flexible than paper books. For readers

not comfortable with electronic systems, there will still exist

bookstores similar to those existing today, but these bookstores

can carry hundreds more titles than they can carry today because

they need only one copy of each. Customers can browse through

this copy as they do today, then have an electronic copy

delivered to them if they decide to buy.

+ Page 18 +

For example, to cater to those customers who dislike

electronic distribution or lack display technology, publishers

can license their list to retailers and have them produce paper

books in the retail outlet on demand. The Kodak Lionheart 1392

costs $199,000 and prints 92 two-sided 300 dots per inch (dpi)

pages a minute; the Xerox DocuTech Production Publisher costs

$220,000 and prints 135 two-sided 600 dpi pages a minute--it can

also collate, saddle stitch, and cover the documents. [11]

If these prices are too high for one publisher or retailer a

consortium of publishers could buy (or lease) printers with each

retailer. These on-demand retailers will save on most of the

costs of contemporary retailers, so publishers may be justified

in charging high licensing fees.

This practice may persist, but since electronic books will

grow out of the linear text-and-pictures format (it is

restrictive and no longer necessary), these customers will be

getting only the flat form of the book. Further, licensing also

works if the retailer produces books on disc, not paper. So

another possible distribution scheme is book dispenser machines

like movie dispenser machines or ATMs, where the user inserts a

disc, has books downloaded to it, and pays for the downloaded

books with a credit card. [12]

4.4 Locked-Disc Publishers

Another way to distribute electronic books is for publishers to

put their entire list on a single disc. Publishers can encrypt

each title separately so knowing the decrypt key for a title

unlocks that title only. Encryption is different from copy

protection; copy protection tries to make information physically

uncopyable, encryption tries to make information unintelligible

without a key. One tries to lock the hardware, the other tries

to lock the software. Both try to deny general access.

These discs can be produced in runs of several thousand at

$1 per disc and could be sold for $5 each. As in the

subscription scheme, publishers could bypass retailers entirely

and sell these discs by mail order. And retailers could increase

title diversity by many thousands; even the smallest retailer

could carry every book ever written since each publisher only

needs one disc. After buying a disc, a reader who wants a

particular title phones the publisher, and the publisher gives

the title's decrypt key then charges the reader's credit card.

Such a scheme is already being tried by font and clip-art

companies. [13]

+ Page 19 +

State of the art encryption schemes are virtually

unbreakable, but once one reader pays for the decrypt key for a

particular title that reader could tell the rest of the world.

So publishers may divide the print run into lots of 100, number

the discs, and change all encrypt keys from one run to the next.

This will increase disc production costs and users would have to

supply the disc lot number when ordering. As with any protection

scheme, cost increases and usability decreases.

Many publishers may choose this scheme since it is most like

their present system, but better. Further, each title is

protected so publishers could increase prices if they choose.

But this scheme, and every other scheme that distributes books on

fixed media, has the problems discussed in the overview and in

the previous section.

4.5 The Future of Retail Books

In the short term, publishers and retailers may promote their

wares direct to readers through media like cable television, the

postal service, and online services, and later, the reader's

portable or home computer. But the need to announce new books

could eventually fade if readers can do their own searching for

books that they may be interested in. Eventually their portable

or home computer could do the searching for them--continuously,

perhaps storing a backlog of books to be considered.

Electronic books are inherently more plastic than paper

books. A decade hence many distribution schemes may coexist:

normal paper publishers, locked or unlocked single-title disc

publishers, on-demand disc or paper publishers, prerecorded full-

list locked-disc publishers, and subscription publishers.

5.0 Changes in Education

A book is a machine to think with. I. A. Richards,

Principles of Literary Criticism.

It is curious that in a supposedly highly literate society a U.S.

hardcover is one of the top 25 bestsellers for the year if it

manages to sell only 115,000 copies--about 1/20th of 1 percent of

the population. Gone With the Wind sold 21 million copies over

40 years, but 55 million people saw the first half of the

television movie. [14] Roots sold 5 million copies over 8 years,

but 130 million people watched 8 episodes of the television

version. The television shows A-Team and Dallas drew 40 and 37

million viewers per episode.

+ Page 20 +

The U.S. has an estimated 13 million illiterate adults.

Since talking books de-emphasize literacy, they may move us

closer to preliterate societies and help to enfranchise the

illiterate, the dyslexic, the blind, the sight-impaired, the

disabled, the elderly, and the young. For publishers, this means

that sales could be higher.

Many believe that the U.S. is facing serious education

problems. Every year 700,000 high-school students drop out,

while another 700,000 graduate unable to read; the percentage of

graduating high-school students has dropped every year since

1984. [15] The social problems causing the drop out rate are

serious and severe and most are unrelated to books, so electronic

books are no cure-all, but they may help reverse the trend.

5.1 Electronic Science Books

Eventually all books will become animated, vocal, and

interactive. Imagine learning orbital mechanics like a video

game where you may choose burn rate and burn time, then have the

book show you what happens to the rocket. Imagine a chemistry

book that lets you bring together different molecules and watch

what the van der Waals forces do to them, following through until

the molecules reach a stable state. Imagine a biology book that

takes you inside a working cell; the book lets you see cell parts

in operation and shows what any part does either normally or

under disease.

Imagine a statistics book that dispenses with artificial

measures like averages and standard deviations and gives the full

data visually. Imagine a mathematics book that lets you to

choose your own parameters for functions and visually shows you

what happens to their derivatives, or lets you dispense with

simplistic models entirely and directly work with simulations.

IBM and the U.S. National Science Foundation are funding work by

the Mathematical Association of America to build interactive

mathematics texts over the next two years. [16]

Imagine a physics book where an apparently alive Galileo,

Newton, or Einstein propounds their various theories then guides

you through developments and consequences, letting you ask

questions or suggest alternatives. As technology improves, you

will be able to change Galileo, Newton, or Einstein to whomever

you wish: perhaps a favorite aunt, a teacher, Bugs Bunny, or

Walter Cronkite.

+ Page 21 +

Imagine a computer architecture book that lets you tour a

computer chip. The book first displays a chip as seen by humans

normally--a black fingernail-sized sliver of shiny silicon. The

book has two controls: a joystick and a light-dimmer switch. As

you move the joystick, the book displays the image you would see

if you were at that distance and point of view.

Pressing down on the joystick brings up a quarter-scale

display in the lower right-hand corner with text, voice, or video

of the author explaining what you are seeing, and telling you

about other things that you might like to see if the current view

interests you. Touching any portion of the screen also pops up a

little window to explain whatever is being displayed at that

place on the screen. The dimmer switch controls the time scale;

twisting it changes the speed at which things happen.

As your viewpoint gets nearer to the surface of the chip,

the chip expands to cover the entire display, then the horizon

disappears off the screen. As you get closer to the surface, you

begin to see pulsating rivers of light representing electron

flows, and you hear a susurrus of sound representing thermal

noise, which later grows to a keening roar as you approach a

river of light. Getting closer to the chip surface and reducing

the time scale you can see individual clumps of electrons

switching through individual gates. The sound has also slowed,

so you can hear each electron whizzing by. Getting even closer

and further slowing the time scale shows a single electron about

to tunnel out of a channel.

This tour book idea works for any physical construct,

natural or artificial. We could have tour books for trees, fire

extinguishers, DNA, motor boats, lungs, car engines, eyes,

televisions, humming birds, space shuttles, whales, or

cyclotrons. More expensive versions of these books could

dispense with the joystick and dimmer switch and instead accept

simple vocal commands: stop, go, faster, slower, zoom here, pan,

undo, reverse, put this there, what is this, show me more, tell

me why.

+ Page 22 +

5.2 Other Educational Books

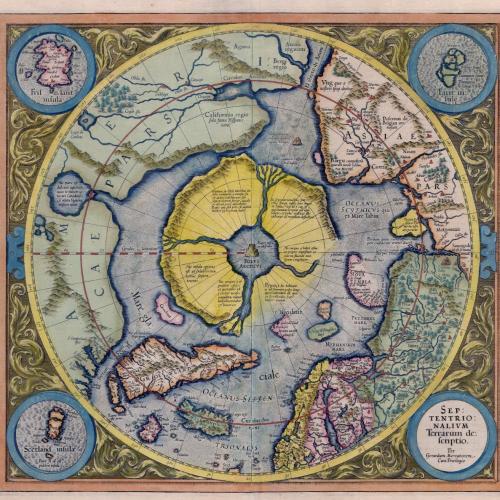

By 2000, the U.S. Geological Survey expects to complete its

national digital cartographic database. This database will

include all the information on the agency's maps, and the agency

is working with the U.S. Census Bureau to integrate demographic

data. [17] Meanwhile, Geovision is selling a U.S. atlas on disc

for $600; on this disc users can zoom down to a city block. And

SilverPlatter is selling a three-disc set for $2,000; the discs

list over 115 million people living in 80 million residences in

the U.S. (Early in 1991, a similar set promoted by Lotus and

Equifax was withdrawn after a blizzard of protest over privacy

issues.)

Imagine an atlas that opens with a rotating globe. (Or an

atlas that begins with a rotating human, library, computer, solar

system, house, car, scanning tunneling microscope, or nuclear

power plant.) You learn about different parts of the globe by

touching it. You can then find out about the geography, history,

geology, climatology, politics, culture, demographics, or

economics of each area. Touching economics might bring up

overlays showing trading partners, trade routes, and goods.

Touching any trade good, from tractors to camcorders, leads to

overlays giving the source of all the raw materials used to make

the good.

Touching a portion of the display gives the history of the

region, its geological background, its demographics, its

transportation system, its climatology, its political allies, its

nearness to major fault lines, its chlorofluorocarbon emission

rate, its projected development over the next five years, its

skin cancer rate over the past ten years and projections for the

next ten assuming various levels of ozone depletion.

Touching another portion lets you extrapolate land use and

deforestation over time to examine the effect of tariffs, or the

effect of waste heat from cities on fish populations, or the

effect of power lines on bird migratory paths, or the effect of

global warming on coastlines and industries. Touching yet

another portion gives pictures of the region's Nobel prize

winners, with their accomplishments and acceptance speeches. Or

pictures of the region's politicians. Or a breakdown of the

region's gross national product decomposed into budgetary

expenditures. Or the effect of solar wind on the region's

satellite reconnaissance. Or the region's offshore natural gas

deposits. Or the epidemiology of retroviral disease. All

portions of the display could be accompanied by movie snippets,

stills, and music.

+ Page 23 +

5.3 The Frailties of Print

An electronic book can be more accurate, more powerful, more

flexible, more informative, more usable, more timely, more

sophisticated, and more adaptable to its user than any number of

paper books. Today an author has to first think of the

questions, research the answers, and find a way to summarize them

in print. With electronic books the user poses the questions--

questions perhaps even the author did not think of--the book

researches the answers--research perhaps almost as good as the

author's own--and the user decides how the information is to be

displayed.

And the same observations hold for books on music, politics,

painting, craftwork, foreign languages, history, zoology,

architecture, geography, design, cooking, hairstyling, self

defense, travel, health, environmental studies, or any other

subject. These books could increase comprehension, retention,

and emotional response without sacrificing convenience,

adjustability, repeatability, searchability, generality, and

abstractability the way that broadcast television does. And

because they are built on top of computers with their great power

for simulation they also add interactivity, testability,

convertability, and projectability.

These books can combine the best aspects of human visual and

auditory presentations, the best aspects of broadcast television,

the best aspects of computers, and the best aspects of print.

Compared to such books, present books are pitiful.

Of course, not all electronic books will be well written;

there will still be poor books and good books--and perhaps in the

same proportion. But even the worst electronic book could be

better than the best paper book, if only because it may be more

easily searched to see if it has anything useful. But, as

always, the sharper the tool, the deeper the cut. Because these

books are more immediate, they can shape our unconscious more

deeply; so bad books could be more dangerous, just as a

demagogue's speech is more compelling than the text of the

speech.

Reading is work, but before writing there was speech,

sounds, and sights. We have had only 5,300 years to get used to

writing, but we have had millions of years to hone our

audiovisual response. Humans are good at interpreting and

relating to audiovisual cues--particularly if they are in control

and can stop, replay, or interact with the action at any time.

Such books will change the way we think, the way we work, and the

way we see ourselves, our artifacts, our governments, and our

world. Every business, every industry, every vocation, every

profession, every educational institution, and every

entertainment group, can use these books to advantage.

+ Page 24 +

Students with books like these are exploring, not reading.

Curiosity motivates them to explore and develop intuition. They

are not intimidated by premature formalism, nor by the artificial

linearity authors are forced to place on a subject just to fit it

into the unnatural format of a paper book. The difference

between these books and paper books is the difference between

behavior and the description of behavior.

Textbooks can move toward this ideal even within the

confines of paper. They can try to: involve the student through

many questions; deformalize the subject until absolutely

necessary through an informal style, cartoons, and many pictures;

show links among different parts of the book through continuous

and exact page referencing; show links among different parts of

the subject through many annotated references; humanize the

author, the book, and the subject through many quotes, quips, and

jokes; and encourage reader exploration.

6.0 The New Publishing

Lead us, Evolution, lead us,

Up the future's endless stair;

Chop us, change us, prod us, weed us.

For stagnation is despair.

C. S. Lewis, "Evolutionary Hymn."

From here on this report focusses on publishers who charge a

monthly fee and who distribute their titles on demand over the

phone. The criteria for judging subscription publishers will be

capital, reputation, and performance. Capital acquires new

product and its amount and liquidity determines credit, which

determines how much expansion there can be, and how fast it can

take place. Reputation and performance assure subscribers of

quality and selection, and attract and retain new authors and

subscribers.

Marketing will also be important. At 3,500 new books a

month and climbing, major book chains and convenience outlets

(convenience stores, drugstores, and supermarkets) now keep new

fiction less than six weeks. Soon paperback fiction may be

monthly--the equivalent of one-shot magazines; eventually

turnover may be weekly.

To pervert Toffler's prediction in Future Shock, [18] in a

decade we will be living in a world of future schlock; 1,000 new

books a day is possible, that is only a factor of eight from

today. Counting all nations, we already produce over 1,000 new

books a day.

+ Page 25 +

6.1 Mapmakers, Ferrets, and Filters

As the number of books published per day mushrooms, the value of

the publisher's editors and their reputation will increase. The

publisher functions as a stamp of approval, a selector, and a

collator. Soon there will be a whole new profession--people who

find things, or know who to ask--perhaps they will be called

ferrets. For those who want to rummage for themselves, there

will be another new profession--people who arrange things--

perhaps they will be called mapmakers. And everyone will need

people who select things--perhaps they will be called filters.

These three professions mirror the three basic aids in

nonfiction books--indices (ferreting), tables of contents

(mapmaking), and bibliographies (filtering)--and the three basic

uses of computers--searching (ferreting), sorting (mapmaking),

and selecting (filtering). All three are marketable services.

Publishers may try to enter all three markets, but unless

they enter them understanding their importance they may be shut

out by more aggressive third-party companies. Eventually they

will also have to compete with computer programs. Word

processors like WordPerfect, spreadsheets like Lotus 1-2-3, and

database programs like dBase are the three biggest reasons

business adopted personal computers. In ten years, ferrets,

mapmakers, and filters may be the equivalent of these programs

today.

As computer power becomes more widespread, each user's

computer may run hundreds of ferret programs continuously, all

separately exploring the world's data for useful information.

When a ferret returns it may have to face dozens of filters who

try to prevent them from adding the data found to the user's

personal information base. Data that enough filters judge to be

important or relevant is passed to the mapmaker to be linked into

the user's personal map of what's important, where it is, and how

it relates to other information in the personal map.

Human beings often use different archival schemes than

print. Librarians are fond of telling horror stories of naive

library users who ask for the large green book on cartoons they

flipped through a month before. But weight, size, smell, and

color of a book are noticed easily, while title, author,

International Standard Book Number, Dewey decimal number, and

Library of Congress number are artificially imposed because they

make easier search keys in traditional databases. The ferret,

filter, and mapmaker programs will benefit those who want to

recall the blue book with the funny picture of President Bush

that Joe lent them.

+ Page 26 +

To most Americans, the 20 million books in the Library of

Congress, perhaps the nation's greatest intellectual resource,

are less useful than a home encyclopedia, because the information

retrieval problem bars access. As books become electronic,

indices, commentaries, databases, annotations, bibliographies,

reviews, concordances, compendia, and selections will be in high

demand. The more data there is, the less information there is;

the more information there is, the less knowledge there is.

To take a household example, partly because they are on

paper the Yellow Pages function poorly. To get the most from

them, the user must understand exactly how the phone company

organized them. The user must also have a detailed map, a subway

guide, bus routes, Consumer Reports, the local Better Business

Bureau Report, and plenty of time.

In addition to an alphabetical listing by type of business,

Yellow Pages should list all businesses on each street, in each

neighborhood, and in each mall; by the time needed to get to them

from the user's current location; by their relation to various

landmarks; by whether they are currently having a sale; by

whether they accept checks, cash, or credit; by their hours of

operation; by their nearness to restaurants, gas stations, public

restrooms, or other stores the user cares about; and by their

expensiveness, reliability, revenue, experience, and returns

policy.

All these ways of organization are possible with electronic

Yellow Pages, and that applies to every other kind of

information. And businesses would pay the mapmaker to be

included, just as they pay credit card companies today, since it

means more business for them. Only five percent of the roughly

6.5 million U.S. businesses advertise outside the Yellow Pages.

6.2 Stage I Penetration

The new technology will first take over technical, professional,

and business knowledge databases, and technical, scientific, and

academic journals for doctors, lawyers, executives, financial

analysts, dentists, scientists, engineers, technicians, and the

professoriate. These people have the need, the money, the

expertise, and the technical infrastructure to support the

technological thrust in the early days.

+ Page 27 +

Already MathReviews exists on disc and it is an enormous

improvement over paper. In 1990, researchers had to wade through

several heavy 1,000-page books full of fine print, imperfectly

indexed and cross-referenced by humans, and out of date because

of the delay. In 1991, these same researchers could search the

entire corpus of published papers--including abstracts, reviews,

comments, and other information not previously included in

MathReviews because of bulk--for arbitrary patterns in seconds.

They no longer even have to go to the library, they can

access it remotely from their home computers. And they no longer

have to use the service during library hours; they can access it

at any time. Further, the library no longer has to find space

for many years worth of 1,000-page MathReviews; they have to keep

only one or two small discs. Finally, the discs are cheaper than

the books they replace. Eventually libraries will not even have

to buy the discs since a few cheap computers could supply the

same information over the phone to the entire world.

Soon universities will start publishing their own electronic

journals. Already publications of the American Chemical Society,

the American Mathematical Society, the American Psychological

Association, the Association for Computing Machinery, the

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, McGraw-Hill,

and Elsevier Science Publishers, are available electronically.

[19] The European Economic Community and the U.S. Office of

Technology Assessment are sponsoring future projects. [20]

Already the Harvard Business Review is available

electronically (there is still a paper version), and the American

Association for the Advancement of Science is publishing the

Online Journal of Current Clinical Trials. Academic libraries

will clamor for electronic versions of all journals, even if

publishers also produce paper versions. Currently, university

libraries have to devote increasing amounts of shelf space and

over half their budgets to journals. The number of academic

journals is doubling every five years, and subscription costs,

already high, continue to rise by ten percent every year.

Full-color professional magazines charge advertisers to pay

authors, publish ten to twelve times a year, and cost consumers

$4 to $6 per issue. Black-and-white academic journals charge

authors to pay printers, publish four to six times a year, and

cost libraries $25 to $400 per issue. Electronic journals would

be cheaper for everyone: publishers, libraries, and readers.

They would also be easier to archive, catalog, and search, less

bulky, more flexible, more expandable, timelier, and larger than

paper journals.

+ Page 28 +

The business community is even more ready to pay a lot for

precious information. In most corporations, middle management

plays the part of ferrets, mapmakers, and filters for senior

management. But paper reports are hard to search, index,

compare, and collate. Further, once a fact, a table, a report,

is committed to paper it is fixed; it cannot be displayed in

alternate and perhaps more accessible forms, like histograms, pie

charts, and graphs. A table listing country populations

alphabetically by country is hard to use when we want to know the

top 50 populations.

In 1986, GTE executives could not easily find information in

their own 200-page financial reports. GTE spent six weeks and

$14,000 to create an Apple HyperCard system that let executives

keep informed about their own business. [21] Ideally, hypertext

should let users chart their own course through the data; text

versus hypertext is like taking a train versus driving a car.

Soon after GTE adopted the system, its president demanded all

reports this way instead of formal presentations from middle

management.

Dow Jones charges $19,600 a year for its CD/Newsline

subscription service: monthly mailings of discs containing public

information about the financial performance of various companies.

[22] Dow Vision delivers news and market information direct to

users' computers for $1,000 a month. [23] Perhaps they get away

with these prices because of the business community's ignorance

of what is possible and what it costs to attain, and the

publishing industry's ignorance of the demand for timely, high-

quality, and electronically-accessible product.

6.3 Stage II Penetration

The new technology will then take over general information

sources: dictionaries, multilingual dictionaries, dictionaries of

quotations, encyclopedias, atlases, almanacs, thesauri,

concordances, phrase books, tourist guides, repair manuals, phone

books, cookbooks, collections of statistics, stock prices,

speeches, operas, paintings, sculptures, magazines, census

information, and library and museum catalogs.

Already the catalog of the Library of Congress, The Readers'

Guide to Periodical Literature, The Oxford English Dictionary,

and Books in Print (at $1,000 a year; with book reviews--

something unthinkable with paper--it is $1,400 a year), are all

available on disc. There are now 1,400 titles available on

compact disc.

+ Page 29 +

The Voyager Company, ABC News Interactive, and Warner New

Media, Incorporated are all producing titles solely for the new

media. For example, in August 1991 the top ten bestsellers (with

some prices) were: Grolier's Electronic Encyclopedia ($400), The

Magazine Rack, The Multimedia World Fact Book, The Microsoft

Bookshelf ($300), U.S. History on CD-ROM, National Geographic's

Mammals, The PC-SIG Library ($500), The Reference Library,

McGraw-Hill's Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, and

Compton's Multimedia Encyclopedia ($900).

Grolie

r's Encyclopedia contains 10 million words and 1,500

pictures; what used to take 21 large books now takes just 1/5th

of one small disc. Compton's Encyclopedia contains 8,784,000

words; 5,200 articles; 15,800 photos, maps, and diagrams; 60

minutes of recorded voices and sounds; 45 animated sequences;

Webster's Intermediate Dictionary (which itself has 65,000

entries); and a word processing program.

Then the new technology will take over textbooks and all

other technical and professional books. Electronically

distributing textbooks could eliminate printing, packaging,

distribution, transportation, postal delay, possible returns,

warehousing costs, and the used textbook industry. And it

reduces both the risk and span of time of having capital tied up

during the distribution process.

6.4 Stage III Penetration

Finally, since electronic books can be interactive, animated, and

vocal they could make serious inroads on fiction. Software

publishers like Broderbund, Voyager, Discis, and Software Mart

and computer/entertainment companies like Sony, Philips-PolyGram,

Britannica Software, Rand-McNally, and Time-Life are seizing the

high ground here, perhaps because traditional publishers lack the

expertise or are not aware of the market.

In October 1991, Voyager introduced interactive forms of

Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Michael

Crichton's Jurassic Park, and The Annotated Alice in Wonderland,

at $19.95 each. These are the first three of Voyager's planned

20 Expanded Book series. Broderbund's Living Books series are

animated children's books scheduled for early 1992 release, the

first three are: Mercer Meyer's Just Grandma and Me, Jack

Perlutski's New Kid on the Block, and Marc Brown's Arthur's

Teacher Troubles, at $49.95 each.

+ Page 30 +

7.0 Gearing Up

All mankind is divided into three classes: those that are

immovable, those that are movable, and those that move.

Arab proverb.

Publishers who are wondering how they can keep things the same

are asking the wrong question. In a rapidly changing

environment, the most important asset is not the present

inventory of skills, but how fast it is improving. Education and

flexibility are essential when what you sell, how you sell it,

who you sell it to, and what they want, are all changing.

7.1 A New View of Economics

Classical economic theory is largely irrelevant to the early

stages of a new information industry. Economics assumes that

resources are finite and that there is enough time for markets to

reach stability. [24] Three things are wrong with this picture:

information is not finite, there is no single stable point--there

are many, and there is little time to reach stability before

there is another major change.

Standard economics applies to finite-resource markets like

agriculture, mining, utilities, and bulk-goods. Such economics

has little to say about information markets like communications,

computers, pharmaceuticals, and bioengineering. These markets

require a large initial investment for design and tooling, but

enormous price reductions with increasing market growth. This

growth is further compounded by positive feedback: with

increasing market growth the production process gets more

efficient, therefore returns increase.

And that growth increases both the number of people

attracted to work on the remaining problems, and the number of

people desiring the improved products. Which in turn fuels the

development of better products. For example, the more people

with facsimile (fax) machines, the more people who wanted fax

machines to talk to those who already had them, and the more

people who had them, the more people who worked to improve them.

Finally, this exponential improvement is being applied to a

group of synergistic technologies; each improvement in one

technology improves other technologies in the group, which in

turn help improve the original technology. For example, better

computers improve communications, which improves science and

engineering, which improves instruments, which improves

computers.

+ Page 31 +

Most U.S. firms seem to see the world in the order:

shareholder, supplier, shopper, staff, society. This order

reflects a world where capital is the most important thing, and

it works well in a stable industrial economy. But in a rapidly

changing industry, placing investors first can lead to short-

sighted financial cannibalism. Instead, in a fast-changing

market, the priorities should be: shopper, staff, society,

supplier, shareholder. The stock market debacles in October

1987, October 1989, and November 1991 show what happens when

short-term gain is valued more than long-term development.

Fortunately the financial markets matter less and less to the

economy; capital will remain important as a risk softener, but

the thing that has become more important to continuous

improvement is knowledge.

Anyone in an information industry who clings to 19th century

techniques is unlikely to survive long. Today, above all else,

it is necessary to be able to cope with change. Achieving this

will take great care since most people are afraid of computers

and of change.

In light of these observations, publishers should acclimate

their staff using internal training programs, salary incentives

for mastering technology, and an internal electronic

communications network. The biggest asset today is a computer-

literate and interacting staff; such a staff is the best source

of ideas on ways to navigate changes. And while other firms can

quickly reverse-engineer and copy systems, technology, and

products, they cannot quickly copy a well-coordinated, committed,

intellectually stimulated, and productive staff. Paradoxically,

because people can no longer change faster than technology a

productive staff is the linchpin of success.

Equipment is now less important than almost anything else

because of plummeting prices and increasing power, flexibility,

robustness, and reliability. Even though the equipment will be

obsolete in 3 years, spending $3,000 per employee to buy

computers and an office network is money well spent. If everyone

gets one and it is presented as a natural change, it is likely

that staff members can help each other over the initial humps--

and there will be many. Once employees start using their

machines for things as approachable as personal electronic mail

to each other their resistance should decrease.

Publishers should also develop a subdivision of one or two

technical people who gather information about and experiment with

different ways of packaging and distributing electronic books.

The subdivision can also function as a source of technical help

for the rest of the company during the transition period, thereby

partly defraying their salary cost.

+ Page 32 +

7.2 Why It Will Work

The subscription scheme will work because many people already pay

for similar services. Many professionals pay over $100 a year

for each of several subscriptions to professional or academic

organizations. For this money they get quarterly journals and

mild discounts on publications that the organization carries

(plus incidental benefits at conferences and so on). Many

professionals pay lawyers and financial advisors annual retainers

for the ability to call on them whenever they wish.

Many people pay over $100 a month in phone bills, and phone

companies charge $30 or more merely to remain connected.

Similarly, millions of people pay $25 or more a month for the

opportunity to watch movies that a cable company chooses, at

times the cable company chooses. Of course, they offer a huge

stock. Publishers can provide better service by letting readers

choose what they read and when, provide a more long-term benefit

to society by benefitting education, science, and technology,

charge each household less per year to do so, and still make

money.

Further, there are now thousands of bulletin boards and

dozens of online services, of which ten are major companies: BIX,

Dialog, Prodigy, CompuServe, Delphi, Reuters, Dow Jones News

Retrieval, GEnie, SprintMail, and Data-Star. In 1990, online

service sales reached nearly $9 billion, almost double 1986

sales.

BIX, the Byte Information Exchange, offers each month's Byte

magazine and other services; its subscription rate is $39 a

quarter, exclusive of phone connect charges. Dialog gives access

to 390 databases, with over 270 million references to over

100,000 publications, including the complete texts of over 1,000

periodicals. Dialog charges anywhere from $45 to $150 for sign

up and connect charges. Prodigy (run by IBM and Sears) has

almost 1 million subscribers, and charges a $50 sign up cost and

$13 per month. CompuServe has 3/4 million subscribers, and

charges a $40 sign up cost and $6 to $22.50 per hour for

connections. Delphi has 100,000 subscribers, and charges $6 a

month and $20 for 20 connect hours.

Finally, in August 1991 after only 2 1/2 years, Waldenbooks

has 4.4 million U.S. readers in their Preferred Reader Program.

Waldenbooks and B. Dalton Booksellers use their programs to keep

track of book buying, title performance, and reader habits, and