Copy Link

Add to Bookmark

Report

Public-Access Computer Systems Review Volume 02 Number 01

+ Page 1 +

----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review

Volume 2, Number 1 (1991) ISSN 1048-6542

Editor-In-Chief: Charles W. Bailey, Jr.

University of Houston

Associate Editors: Columns: Leslie Pearse, OCLC

Communications: Dana Rooks, University of

Houston

Reviews: Mike Ridley, University of Waterloo

Editorial Board: Walt Crawford, Research Libraries Group

Nancy Evans, Library and Information

Technology Association

David R. McDonald, Tufts University

R. Bruce Miller, University of California,

San Diego

Paul Evan Peters, Coalition for Networked

Information

Peter Stone, University of Sussex

Published on an irregular basis by the University Libraries,

University of Houston. Technical support is provided by the

Information Technology Division, University of Houston.

Circulation: 2,685 subscribers in 32 countries.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Editor's Address: Charles W. Bailey, Jr.

University Libraries

University of Houston

Houston, TX 77204-2091

(713) 749-4241

LIB3@UHUPVM1

Articles are stored as files at LISTSERV@UHUPVM1. To retrieve a

file, send the GET command given after the article information to

LISTSERV@UHUPVM1. To retrieve the article as an e-mail message

instead of a file, add "F=MAIL" to the end of the GET command.

Back issues are also stored at LISTSERV@UHUPVM1. To obtain a

list of all available files, send the following message to

LISTSERV@UHUPVM1: INDEX PACS-L. The name of each issue's table

of contents file begins with the word "CONTENTS."

Note that all of the above e-mail addresses are on BITNET. The

list server also has an Internet address:

LISTSERV@UHUPVM1.UH.EDU.

+ Page 2 +

CONTENTS

SPECIAL SECTION ON NETWORK-BASED ELECTRONIC SERIALS

The Electronic Journal: What, Whence, and When?

Ann Okerson (pp. 5-24)

To retrieve this file: GET OKERSON PRV2N1

Online Journals: Disciplinary Designs for Electronic Scholarship

Teresa M. Harrison, Timothy Stephen, and James Winter

(pp. 25-38)

To retrieve this file: GET HARRISON PRV2N1

Post-Gutenburg Galaxy: The Fourth Revolution in the Means of

Production of Knowledge

Stevan Harnad (pp. 39-53)

To retrieve this file: GET HARNAD PRV2N1

The Journal of the International Academy of Hospitality Research

Lon Savage (pp. 54-66)

To retrieve this file: GET SAVAGE PRV2N1

Postmodern Culture: Publishing in the Electronic Medium

Eyal Amiran and John Unsworth (pp. 67-76)

To retrieve this file: GET AMIRAN PRV2N1

New Horizons in Adult Education: The First Five Years (1987-1991)

Jane Hugo and Linda Newell (pp. 77-90)

To retrieve this file: GET HUGO PRV2N1

EJournal: An Account of the First Two Years

Edward M. Jennings (pp. 91-110)

To retrieve this file: GET JENNINGS PRV2N1

The Newsletter on Serials Pricing Issues

Marcia Tuttle (pp. 111-127)

To retrieve this file: GET TUTTLE PRV2N1

+ Page 3 +

COMMUNICATIONS

How to Start and Manage a BITNET LISTSERV Discussion Group: A

Beginner's Guide

Diane Kovacs, Willard McCarty, and Michael Kovacs (pp. 128-143)

To retrieve this file: GET KOVACS PRV2N1

Providing Data Services for Machine-Readable Information in

an Academic Library: Some Levels of Service

Jim Jacobs (pp. 144-160)

To retrieve this file: GET JACOBS PRV2N1

COLUMNS

Public-Access Provocations: An Informal Column

Depth vs. Breadth: Enhancement and Retrospective Conversion

Walt Crawford (pp. 161-163)

To retrieve this file: GET CRAWFORD PRV2N1

Recursive Reviews

Copyright, Digital Media, and Libraries

Martin Halbert (pp. 164-170)

To retrieve this file: GET HALBERT PRV2N1

REVIEWS

Libraries, Networks and OSI: A Review, with a Report on

North American Developments

Reviewed by Clifford A. Lynch (pp. 171-176)

To retrieve this file: GET LYNCH PRV2N1

+ Page 4 +

The User's Directory of Computer Networks

Reviewed by Dave Cook (pp. 177-181)

To retrieve this file: GET COOK PRV2N1

----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is an electronic

journal. It is sent free of charge to participants of the

Public-Access Computer Systems Forum (PACS-L), a computer

conference on BITNET. To join PACS-L, send an electronic mail

message to LISTSERV@UHUPVM1 that says: SUBSCRIBE PACS-L First

Name Last Name.

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is Copyright (C) 1991

by the University Libraries, University of Houston, University

Park. All Rights Reserved.

Copying is permitted for noncommercial use by computer

conferences, individual scholars, and libraries. Libraries are

authorized to add the journal to their collection, in electronic

or printed form, at no charge. This message must appear on all

copied material. All commercial use requires permission.

----------------------------------------------------------------

+ Page 67 +

----------------------------------------------------------------

Eyal Amiran and John Unsworth. "Postmodern Culture: Publishing

in the Electronic Medium." The Public-Access Computer Systems

Review 2, no. 1 (1991): 67-76.

----------------------------------------------------------------

1.0 Introduction

Postmodern Culture was founded in 1990 by Eyal Amiran, Greg

Dawes, Elaine Orr, and John Unsworth at North Carolina State

University (professors Dawes and Orr have subsequently stepped

down as editors in order to pursue their research projects,

though both remain on the editorial board).

Postmodern Culture is a peer-reviewed electronic journal which

provides an international, interdisciplinary forum for

discussions of contemporary literature, theory, and culture. It

accepts for consideration both finished essays and working

papers, and carries in each issue fiction and/or poetry, book

reviews, a popular culture column, and announcements. The

journal does not consider essays dealing exclusively with

computer hardware or software, unless those essays raise

significant aesthetic or theoretical issues.

PMC comes out three times a year (September, January, and May)

and is free to the public and to libraries via electronic mail.

Each issue of Postmodern Culture carries a volume and number

designation. The journal is also available on computer diskette

and microfiche; it is distributed in a variety of diskette

formats (Macintosh 3.5", IBM 5.25", or IBM 3.5"), but no issue

will exceed 720 KB of data, the equivalent of one 3.5" or two

5.25" low-density diskettes. The subscription rate for diskette

or microfiche is $15/year for individuals, $30/year for

institutions (in Canada add $3; elsewhere outside the U.S. add

$7). At the present time PMC has about 1,200 subscribers in 17

countries. The journal's ISSN number is 1053-1920.

The editorial board for Postmodern Culture includes researchers

and writers in African American studies, cultural studies, film,

Latin American studies, literature and literary theory,

philosophy, sociology, and religion.

+ Page 68 +

The board members' primary responsibilities include reading

essays for the journal (approximately four essays a year),

inviting submissions, and helping to publicize the existence of

the journal. Some have also contributed essays. Members were

chosen because of their own performance in their field (or the

promise of it--we chose some younger scholars who were highly

recommended by their colleagues) and because they offer special

knowledge of diverse disciplines, genres, and cultures.

The first volume (numbers 1-3) of the journal included essays on

Latin American politics, eating disorders and spiritual

transcendence, the theory of writing in the hypertext

environment, William Gaddis's novel JR, the implications of the

postmodern critique of identity for the Afro-American community,

the rhetoric of the Persian Gulf War as presented in the New York

Times, the politics of Sartre, AIDS and cyborgs, Ishmael Reed's

The Terrible Two's, and representations of mass culture,

postmodern ethnography, and other subjects.

The journal has also published popular culture columns on the

televising of the Tour de France, Satanism and the mass media,

and female body building, plus fiction by Kathy Acker, a hybrid

theoretical-interpretive-poetic work by Susan Howe, a video

script by Laura Kipnis, and a number of poems and book reviews.

2.0 Distribution

When an issue is published, its table of contents is distributed

(using the Revised LISTSERV program) to all of the journal's

subscribers. This file contains the journal's masthead,

information about subscription and submission, the names of

authors published in that issue, and titles, filenames, and

abstracts for each item in the issue.

Subscribers can then choose to retrieve one essay, several

essays, or the whole issue as a package, using a few simple

LISTSERV commands (it is not necessary for individual subscribers

to have a copy of the LISTSERV program running at their site in

order to issue these commands). Essays can be retrieved as files

or as mail, and all essays are stored in a file list maintained

on the NCSU mainframe, so readers can get copies of material

published in back issues at any time.

+ Page 69 +

We have found the LISTSERV program to be an extremely flexible

and effective way to publish in this medium. It is widely used,

and it is generally familiar to those who already participate in

network discussion groups. It is also well-documented, and

support for list owners is available both locally (from the

postmaster and support staff at one's site) and through an

electronic discussion group moderated by Eric Thomas, who wrote

the program.

LISTSERV lists can be set up in different ways. For instance,

one can set up a list so that all mail posted to it is

automatically distributed to all subscribers, or so that all mail

posted to the list is sent to the list editor for screening

and/or compilation. Subscription to the list can be open or

restricted, as can access to the names of other subscribers and

to any files stored in association with the list. Furthermore,

the ability to edit files on the file list can be limited to the

editors, permitted to a designated group of readers, or permitted

to all readers. List maintenance and list editing can be

performed by different people (or by a number of people) at the

same site or at different sites, and one can automate certain

functions, such as the distribution of a designated set of files

for new subscribers.

Postmodern Culture is open to public subscription, and its

archived files are available for retrieval. Mail cannot be sent

directly for distribution to the list. Only the editors post and

edit items and maintain the list.

3.0 History

Some of our earliest discussion focused on the format in which we

might distribute the journal. We considered various analogues

and models for what we wanted to do, including interactive

software such as electronic bulletin boards (for example, the

Electronic College of Theory), hardware- or software-specific

journals such as TidBITS (a HyperCard, Macintosh-based journal),

and network discussion groups (such as HUMANIST).

+ Page 70 +

We decided that restricting ourselves to the lowest common

denominator would increase our accessibility and make us

available to a wider pool of subscribers. For these reasons, we

settled on ASCII text transmitted by electronic mail as our

format. ASCII text can be imported into almost any word

processing program, and electronic mail can be delivered free of

charge through Internet and BITNET, networks which connect

thousands of sites around the world.

Our next logistical decision was to set up PMC-Talk, a discussion

group which supplements the journal with an open channel for

critique, informational exchanges, and the publication of

non-juried submissions.

Finally, we elected to make the journal available on disk and

microfiche, so that libraries which could not devote the hardware

to making the journal available in its electronic mail form could

still subscribe, and so that individual users who had no access

to electronic mail could still have access to us.

During the Spring of 1990, we mailed several hundred letters to

artists, scholars, and critics in a wide variety of fields.

These letters met with a remarkably positive reception, and

enabled us to assemble a first-rate editorial board and a very

interesting first issue within a period of months. The response

to our mailings is a strong indication that many humanists are

prepared for the advent of electronic publication, and are eager

to learn more about the possibilities of the medium.

The response we met with at our own institution has been equally

encouraging. We have received financial and technical support

from several parts of North Carolina State University (NCSU): the

Computing Center, the Humanities Computing Lab, the Social

Sciences Computing Lab, the Department of English (which has

agreed, for instance, to give course reductions to the editors),

the Department of Foreign Languages, the College of Humanities

and Social Sciences, and the NCSU Libraries.

+ Page 71 +

4.0 Standards and the Medium

One of the questions we have considered in the course of putting

together the first three issues is whether the medium in which we

publish is particularly appropriate to a certain kind of essay.

Is the "finished" work more appropriate in the print medium,

while works in progress, collaborative essays, and interviews are

more appropriate for an electronic journal? Or, is there room

for both in this medium? Might the common sense of what it is

that constitutes a finished work itself be transformed when the

journal invites and publishes responses to the essay, and these

appear only days after the essay had been published?

Postmodern Culture can serve to encourage more experimental

scholarly writing. For example, we publish works-in-progress,

such as Bell Hooks's investigation of the interrelations and

contradictions of African American culture and postmodern theory,

which invite discussion and allow scholars to open their work to

criticism as they write, so that texts may in fact evolve as

collaborative ventures between readers and writers. We have also

published works which fall between or outside traditional generic

categories, like a video script by Laura Kipnis, which

literalizes the metaphor of the body politic, mixing a

biographical account of Marx's health problems during the writing

of Das Kapital with a discussion of contemporary anorexia and

bulimia.

We've also had to grapple with some more mundane questions which

are nonetheless still quite important, since there is very little

in the way of history or tradition to draw on. For example, how

should we format the essays published in the journal so that they

can be easily imported into whatever word processing software the

reader might have? Margins, spacing, the designation of units of

text, typographical conventions for underlining, boldfacing,

italics, superscript, and subscript (these are not possible with

ASCII text), must all be developed and tested with different

users before we will know what works, what is clearly readable

and understandable, and what users prefer.

+ Page 72 +

There are several other technical questions as well. For

example, every issue of the journal will have to navigate the

sometimes obscure connections between different

networks--particularly between the non-commercial academic

networks and the more widely available commercial carriers of

electronic mail, such as MCI, AT&T, Sprint, and CompuServe.

CompuServe, for example, limits the size of electronic mail

transmissions which can be received into individual accounts, and

that limit is well below what would be necessary to receive the

journal.

We are concerned that the journal should be available to

non-academic subscribers, so we will be working to make existing

connections work and to open new ones. We will also be exploring

possibilities for using visual materials, which include faxing

graphics to subscribers on request or transmitting through the

networks compressed graphics files in commonly used formats.

As the networks update their own hardware (especially with

the introduction of fiber-optic cables for data transmission),

new possibilities in the use of interactive software will also

become available. All of this makes it likely that the format

and the nature of Postmodern Culture will continue to evolve,

even in the immediate future. We have learned from print

publication to work around problems and limitations in production

and dissemination, but these problems do not pose as serious a

threat to electronic publishing. Electronic technology is

evolving so quickly--compare current desktop technology with that

available ten years ago--that today's problems (e.g.,

distributing graphics over the nets) will in all likelihood be

solved soon. We do not need to develop standards and techniques

that accept today's limitations, but to build into our medium a

flexibility that will anticipate and accommodate upcoming change.

5.0 The Future of Electronic Serials

In order for a publication in electronic media to succeed in

serving even the most traditional purposes, such publication

obviously needs to be available to the public--to students, to

researchers, and to interested readers.

+ Page 73 +

An electronic publication can keep its back issues on a file list

(an electronic log of reserved files) where network users may

retrieve them, but not everyone has access to the networks, and

there is no guarantee that a file list maintained by a given

electronic mail account-holder will always be there. If a

journal moves to another institution or ceases publication, how

will researchers have access to essays published by the journal?

In the same way they do for print journals, libraries should

provide that access. Many libraries have local area networks and

can make electronic publications available to patrons on those

networks; many more libraries have online card catalogs, and

might use some of those terminals to provide access to electronic

texts. It makes sense for libraries to use computer resources to

deliver publications which originate as electronic text, since

computerized access brings with it powerful capabilities for

searching, indexing, and analyzing texts even from remote sites.

However, until most libraries have the facilities to present full

text online and most readers have the skills to use such

services, we feel that it is important for electronic

publications to be available in several formats.

Electronic publications are likely to proliferate sooner than

most now expect. Although electronic text may never replace

print, it is likely to dominate where information storage,

retrieval, and manipulation are more important than the aesthetic

qualities of a printed text. Economic reasons alone will force

letters out of their time-honored sanctuary in wood-products and

into the electronic ether. It will soon seem as illogical to

print archives, data banks, government and business documents,

and much scholarly material as it already is to catalog the

holdings of large libraries on three-by-five cards.

Today, we still produce limited numbers of books whose physical

well-being must be guarded at regulated institutions around the

world. We must have these objects shipped to us or travel to

centers where they are collected. Compare this to a situation

where a library would not house a given number of volumes, but

would provide access to all books in an international network of

libraries. In this scenario, all books would be available to

anyone with a library card. Even the aesthetic appeal of

electronic text is bound to improve as computer equipment becomes

more portable, more sophisticated, and simpler to use.

+ Page 74 +

Such revolutionary flexibility holds dangers too--technological

freedom and the control of information may be flip and flop of

the same switch. For example, if commercial organizations step

into academic electronic publishing, then they may come to limit

redistribution of such publication or insist on copyright

restrictions that may serve their financial interests but not the

interests of the research community. In effect, this is the case

with print publication: much of it is determined by the financial

interests and possibilities of commercial presses--a condition

which seems so inevitable that it is virtually transparent.

Highly developed technological flexibility may depend on

private-sector support in the long run. The government now

subsidizes the networks, but threatens to cut its support by the

end of the decade. It is hard to say if and how the financial

support and interests of commercial enterprises will affect the

contents and availability of electronic serials. The nets now

offer an ideal international venue for small-budget,

limited-interest discussion groups and serials that may not have

had a chance for wide distribution in print, but all this may

change if the nets go private.

6.0 Conclusion

Electronic publishing needs the encouragement and participation

of the profession so that it leads where we want to go.

Libraries should take an active role in making electronic

publications--journals now, books in all likelihood

later--available to their users; universities should recognize

scholarly activity in the electronic field and see their support

of such developments as wise investments; and the profession

should recognize the legitimacy of electronic publications where

issues of tenure and promotion are involved.

For their part, the publishers of refereed electronic

journals--and of other electronic work in the future--should both

work to maintain professional credibility and take into account

the needs of an audience that is likely to be diverse and large.

+ Page 75 +

Selected Bibliography

Bailey, Charles W., Jr. "Intellectual Property Issues."

Electronic mail message to the Association of Electronic

Scholarly Journals list, 1 January 1991. BITNET, AESJ-

L@ALBNYVM1, GET AESJ-L LOG9101 to LISTSERV@ALBNYVM1.

Engst, Adam C. "TidBITS#30/Xanadu_text." Electronic mail message

to the Machine-Readable Texts list, November 1990. BITNET,

GUTENBERG@UIUCVMD, GET GUTNBERG LOG9011 to LISTSERV@UIUCVMD.

Herwijnen, Eric van. Practical SGML. Geneva, Switzerland:

Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1990.

Jennings, Ted. "Electronic publishing." Electronic mail message

to the Association of Electronic Scholarly Journals list, 30

December 1990. BITNET, AESJ-L@ALBNYVM1, GET AESJ-L LOG9012 TO

LISTSERV@ALBNYVM1.

Kulikowski, S. "Network Reference and Publication." Electronic

mail message to Educational Technology list, October 1990.

BITNET, EDTECH@OHSTVMA, GET EDTECH LOG9010 to LISTSERV@OHSTVMA.

Lambert, Jill. Scientific and Technical Journals. London: Clive

Bingley, 1985.

Ulmer, Gregory. "Grammatology Hypertext." Postmodern Culture

1, No. 2 (January 1991). BITNET, GET ULMER 191 PMC-LIST to

LISTSERV@NCSUVM.

+ Page 76 +

About the Authors

Eyal Amiran and John Unsworth

Postmodern Culture

Box 8105

North Carolina State University

Raleigh, NC 27695

PMC@NCSUVM

----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is an electronic

journal. It is sent free of charge to participants of the

Public-Access Computer Systems Forum (PACS-L), a computer

conference on BITNET. To join PACS-L, send an electronic mail

message to LISTSERV@UHUPVM1 that says: SUBSCRIBE PACS-L First

Name Last Name.

This article is Copyright (C) 1991 by Eyal Amiran and John

Unsworth. All Rights Reserved.

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is Copyright (C) 1991

by the University Libraries, University of Houston, University

Park. All Rights Reserved.

Copying is permitted for noncommercial use by computer

conferences, individual scholars, and libraries. Libraries are

authorized to add the journal to their collection, in electronic

or printed form, at no charge. This message must appear on all

copied material. All commercial use requires permission.

----------------------------------------------------------------

+ Page 177+

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review 2, no. 1 (1991):

177-181.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

-----------------------------------------------------------------

LaQuey, Tracy L., ed. The User's Directory of Computer Networks.

Bedford, MA: Digital Press, 1990. ISBN: 1-55558-047-5. $34.95.

Reviewed by Dave Cook.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

In the introduction to her book, The User's Directory of Computer

Networks, Tracy LaQuey points out that this is not a book to be

read from cover to cover, but rather one to be consulted and used

as "a central reference guide." The User's Directory of Computer

Networks is a directory and, therefore, is primarily useful for

finding discrete pieces of information on networks and

networking. However, a good deal of it can be read with interest

and pleasure, especially by those with an historical interest in

computer-mediated communication and computer networks. Sections

of it should be read with care to facilitate its use a directory

and an information source.

The book was influenced by John Quarterman's book The Matrix and

by his earlier article on networking distributed on the networks

and published in Communications of the ACM in 1986. The LaQuey

and Quarterman books are basic works for a reference section on

computing, CMCS, and networks.

The Directory is itself based on earlier, annual publications and

is an updated expansion of the 1989 guide published by the

University of Texas at Austin. The earlier editions are still

available online and can be consulted by those who wish to check

the general outline and approach to the present edition. The

address is EMX.UTEXAS.EDU; login anonymous. Use the

NET.DIRECTORY for the introductory material and the

NET.DIRECTORY/1988.NETBOOK for the several files of the text

proper.

The Directory is organized in broad sections, each representing a

major network system (i.e., BITNET, DECnet Internet, Internet,

JANET, and USENET). There are also sections on UUCP, domains,

the OSI/x.500 standards, electronic mail, and a list of

organizations. The selection criteria were the size and scope of

the network listed and, interestingly, the responsiveness of the

network contact.

+ Page 178 +

There is no index, but its lack is not as important as might be

thought at first glance. The detailed "Contents" section

outlines the major networks and lists the subnets associated with

them. It is quite easy to find the particular one you're looking

for. The "List of Organizations" section is useful both as a

list and as a finding aid.

The international scope of the Directory is very apparent here.

It is a surprise to realize just how many institutions, both

academic and commercial, are integral components of these

networks and, one assumes, are using them as a standard part of

their institutional life.

The "List of Organizations" is also a cross-referenced finding

aid that can be used to locate the network associated with the

institution you are interested in. Brief instructions on how to

do this are mentioned in the "Introduction" and should be read

first by anyone wanting to make full use of the directory. You

are advised to look up your own organization in the "List of

Organizations" and to trace its connectivity through the

appropriate sections of the book. It's good advice, and it does

reveal the practical design of the book and how useful it can be

in real situations. The entries give a lot of information in

very little space: a description of the equipment, network, and

mail addresses; a contact person; and, useful when all else

fails, a phone number. Finding a personal address is still not

easy; you are left knowing the address of your correspondent, but

still guessing at his or her ID. The solution to that problem

will have to wait for a phone book to be published rather than a

directory of sources. The Directory is not a phone book, but it

does take you several steps along--the right-hand side of the

address and the syntax are now apparent and the postmaster's ID

is listed.

Much of the information for the Directory came from the

information databases maintained at the individual Network

Information Centres. The editor mentions an "accelerated editing

process" which means that some of the detail was not checked or

verified further. Readers are encouraged to send corrections to

the NIC's for their network (the address is provided) and to send

corrections, suggestions, or comments to the editor to be used in

future editions of the book.

In imposing a uniform format on the entries and collecting the

data in one large volume, the editor has created one place to

look for detailed information and has created a very useful tool

for e-mail and network enthusiasts. The consistent format adds

considerably to the ease of use of the Directory.

+ Page 179 +

LaQuey also stresses a concept called "Directory Services." That

is, the creation of a resource guide that can be used for more

than basic address information. The Directory has been designed

to help the user to locate resources in the broader sense:

contact names, database information, computer resources and the

availability of OPAC's and catalogues. Explicit data in these

areas is not provided, but the information given will allow the

individual researcher to take the initial steps towards locating

more information. Art St. George's work on OPAC's and the

various "Lists of Lists" for computer conferences on the networks

will still be primary sources in this area. The LaQuey book

expands their usefulness by detailing and explaining the

framework within which they operate.

There is another dimension to the Directory that makes it

interesting to read as well as informative. Short essays have

been included to introduce each of the major sections. The one

on BITNET is representative, with lots of technical information

written an a non-technical, easy to read style. A brief,

historical overview and a detailed geographic map showing the

sites and the interconnecting store-and-forward routes gives a

useful overview. A description of the general services provided,

a list of network information materials and instructions on how

to retrieve them, and an explanation of the commands and syntax

for IBM and VAX users are useful. An extensive list of BITNET

representatives is also included. This introduction is another

area where an international dimension to networking is very

apparent. EARN, NetNorth, and BITNET form one logical network

and the degree of international cooperation that underlies that

political fact is striking.

The section on the Internet follows the same pattern in combining

history (and a glimpse at the future) with descriptions of

technical processes providing a non-technical overview. The page

on protocol suites gives an explanation of concepts, such as

TCP/IP, and it provides a place to look it up when I, once again,

forget the details.

+ Page 180 +

These introductory essays are often written by experts--John

Quarterman on electronic mail and Eugene Spafford on The USENET

and UUCP, for example. Quarterman's article and his idea that

electronic mail is the glue that holds networking systems

together will be familiar to readers of The Matrix. The brief

summary here is appropriate and the explanation of domains and

gateways is helpful. One can only agree with the author the "the

current mess [mail addressing conventions] is not ideal" and that

"A generally accepted addressing syntax is the only real

solution."

Eugene Spafford writes clearly on USENET and UUCP. Those of us

who have absorbed BITNET and Internet procedures as the

networking norm will find the idea of no central authority and no

backbone structure a bit mystifying. The apparent anarchy of no

(or very few) rules for members or participants does have a charm

of its own. The processes are so complex and the scale is so

vast, that the wonder is that the system works at all.

The User's Directory of Computer Networks is useful, of course,

in the reference section of any library or academic department

concerned with local, national, or international networking. It

should also be useful for non-academic users. For example,

managers of large, national bulletin board systems who

incorporate network mail and conferences into their services.

Computer enthusiasts looking for help with the next step in their

development of personal knowledge and skills will also find the

Directory a great help.

+ Page 181 +

About the Author

Dave Cook

McMaster University Library

Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

COOKD@MCMASTER

----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is an electronic

journal. It is sent free of charge to participants of the

Public-Access Computer Systems Forum (PACS-L), a computer

conference on BITNET. To join PACS-L, send an electronic mail

message to LISTSERV@UHUPVM1 that says: SUBSCRIBE PACS-L First

Name Last Name.

This article is Copyright (C) 1991 by Dave Cook. All Rights

Reserved.

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is Copyright (C) 1991

by the University Libraries, University of Houston, University

Park. All Rights Reserved.

Copying is permitted for noncommercial use by computer

conferences, individual scholars, and libraries. Libraries are

authorized to add the journal to their collection, in electronic

or printed form, at no charge. This message must appear on all

copied material. All commercial use requires permission.

----------------------------------------------------------------

+ Page 161 +

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review 2, no. 1 (1991):

161-163.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Public-Access Provocations: An Informal Column

-----------------------------------------------------------------

"Depth vs. Breadth: Enhancement and Retrospective Conversion"

by Walt Crawford

'Way back in 1987, I wrote: "Most patrons will use only one

catalog, particularly if they find any results. Adding more

material to the online catalog is more important than adding more

information to existing records. Budgetary realities suggest

that libraries can either include more items in online catalogs

or enhance the contents of some items, but probably not both"

[1].

I don't believe the budgetary realities have changed all that

much since 1987; if anything, they've grown worse. The miracle

cure for retrospective conversion has proved as elusive as other

miracle cures: doing it right takes time and money, period. The

same goes for any miraculous means of enhancing access (e.g.,

adding chapter titles, tables of contents, or back-of-book index

entries to OPAC records).

Thus, the easy answer to the question, "if we knew 20 years ago

what we needed to do to improve subject access, why haven't we

done it" is that it doesn't--and shouldn't--have first priority.

If It Isn't in the Catalog, It Isn't in the Collection

That's the simplest statement of one problem, but it's at most a

very slight exaggeration. If you don't agree with that premise,

then there's nothing more to say: we're living in different

worlds.

+ Page 162 +

Is it more important to have in-depth access to a small part of

the collection, rather than normal bibliographic access to all of

it? Some people apparently think so. Some of the most dogged

advocates of enhanced access have suggested eliminating all

subject access for materials more than 10 years old--and

possibly taking 20-year-old materials out of the catalog

altogether. So much for retrospective conversion--and you can

save big bucks by shutting down preservation departments as well!

To be fair to these advocates, I think they're trying to solve a

different problem--the fact that precision goes down as recall

goes up, and at some point lack of precision makes recall

worthless--but the effect is the same: they're proposing

something akin to discarding older materials in the interest of

better access to the new.

I'm a bit suspicious of the idea that every discipline (or, for

that matter, any discipline) reinvents itself every decade.

Perhaps that's because my degree is in rhetoric, but even

cellular physicists might be a tad uncomfortable with the idea

that nothing published prior to 1981 is worth reading. Let's not

talk about where that leaves librarianship; at least all those

who have never read Ranganathan, Cutter, or Dewey would no longer

be bashful about it.

If we're not willing to off the old books, then we must grant

them the respect they're due, which means inclusion in the online

catalog. Once that's completed, and once we're sure that new

materials will get into the online catalog promptly, then we can

and should spend more time enhancing certain categories of

records. The USMARC format already provides good storage

mechanisms for some such enhancements; all it takes is time and

money. Meanwhile, I find it hard to fault real-world libraries

for their current priorities: putting it all into the online

catalog at current levels of access, rather than giving some

material (who chooses?) special treatment while leaving other

material out altogether. That's responsible librarianship.

Notes

Walt Crawford, Patron Access: Issues for Online Catalogs (Boston,

MA: G. K. Hall, 1987), 21.

+ Page 163 +

About the Author

Walt Crawford

The Research Libraries Group, Inc.

1200 Villa Street

Mountain View CA 94041-1100

BR.WCC@RLG.BITNET

----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is an electronic

journal. It is sent free of charge to participants of the

Public-Access Computer Systems Forum (PACS-L), a computer

conference on BITNET. To join PACS-L, send an electronic mail

message to LISTSERV@UHUPVM1 that says: SUBSCRIBE PACS-L First

Name Last Name.

This article is Copyright (C) 1991 by Walt Crawford. All Rights

Reserved.

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is Copyright (C) 1991

by the University Libraries, University of Houston, University

Park. All Rights Reserved.

Copying is permitted for noncommercial use by computer

conferences, individual scholars, and libraries. Libraries are

authorized to add the journal to their collection, in electronic

or printed form, at no charge. This message must appear on all

copied material. All commercial use requires permission.

----------------------------------------------------------------

+ Page 164 +

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review 2, no. 1 (1991):

164-170.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Recursive Reviews

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Copyright, Digital Media, and Libraries

by Martin Halbert

Running a branch library devoted to computational materials, I am

frequently amazed at patrons' lack of understanding of copyright

issues. One patron, an otherwise very intelligent research

scientist, was baffled concerning the restrictions inherent in

checking software out of the library. The magnitude of his

misunderstanding came home to me when he asked if our

restrictions meant that he didn't need to bring his own disks to

copy the software onto. He thought, in all honesty, I finally

realized, that copying the software was what checking out

software was all about. After a very long discussion with him

about copyright and why it is illegal to copy software, he went

away somewhat shocked, but at least informed.

While most librarians have a better understanding of the concept

of copyright than my patron, how many of us have really thought

about all the ramifications of copyright and new digital media

technologies? Librarians are ostensibly supposed to be experts

on the proper use of the collections of information they

administer. This month's column is devoted to a brief

bibliography on the subject of copyright and digital media. I

know that I had never considered many of the issues raised in the

sources reviewed below, so I think they will be of interest to

all librarians who have added any kind of digital media (e.g.,

software and CD-ROM databases) to their collections.

+ Page 165 +

-----------------------------------------------------------------

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Intellectual

Property Rights in an Age of Electronics and Information.

Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1986.

OTA-CIT-302.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

This 1986 report by the Office of Technology Assessment is the

best existing review and discussion of how new technological

developments have impacted the concept of intellectual property

in the United States. Many discussions of the topic begin with a

review of this source (see below), which is justifiable

considering its quality. The 300-page report concisely covers

the conceptual framework and goals of intellectual property

rights, how current laws have tried to accommodate technological

change, enforcement issues, and the role of the federal

government as a regulator. The conclusion of the report is that

the new technologies, especially functional works like software,

have rendered the existing concepts and implementations of

domestic intellectual property law obsolete. An entirely new

approach to the issue of what constitutes intellectual property

and how to regulate it will have to be developed by congress.

The OTA report raises profoundly troubling issues for librarians

and the entire information industry.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Computer

Software and Intellectual Property--Background Paper.

Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, March 1990.

OTA-BP-CIT-61

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Drawing on the 1986 OTA report and others, this OTA background

paper further analyzes software issues. It goes into greater

detail concerning questions peculiar to software, such as

addressing the following questions. Can an interface be

copyrighted? Can the concept of an algorithm be unambiguously

defined? Patented? Is a neural net to be considered a software

system or a hardware system? The paper includes a few

developments which happened after the 1986 OTA report, but

fundamentally the paper only raises questions and provides a

context for discussing the problem. Real answers may be a long

way off.

+ Page 166 +

----------------------------------------------------------------

Duggan, Mary Kay. "Copyright of Electronic Information: Issues

and Questions." Online 15, no. 3 (May 1991): 20-26. (ISSN

0146-5422)

----------------------------------------------------------------

Because developments in the law have lagged so far behind

technological developments, many issues of copyright and digital

media are being resolved in practice, if not in legal fact.

Duggan discusses emerging views about what constitutes "fair use"

of electronic information sources. She concludes that while some

consensus is developing about use of search results from CD-ROM

and dial-up databases, little agreement has yet been reached

about LAN and WAN access to databases and other network

information sources.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Garret, John R. "Text to Screen Revisited: Copyright in the

Electronic Age." Online 15, no. 2 (March 1991): 22-24. (ISSN

0146-5422)

----------------------------------------------------------------

John Garret is the director of market development at the

Copyright Clearance Center. Taking a very different view from

most of the other sources reviewed in this column, he maintains

that current copyright laws are perfectly capable of dealing with

the new electronic environment. He calls into question many of

the assumptions about computer systems and monetary funding that

(he claims) underlie the move to overhaul the copyright system.

He describes a variety of small-scale pilot projects that the

Copyright Clearance Center has undertaken in conjunction with

publishers and researchers "to provide owner-authorized,

text-based information electronically for internal use to various

sets of users, and to determine what they use, when they use it,

why, how often, and to what end." He further claims: "For these

pilots, and for other, larger-scale programs that will be

developed in the future, existing copyright law provides a

perfectly adequate context for the development and elaboration of

systems to manage computer-based text."

+ Page 167 +

While one has to wonder whether Mr. Garret is unbiased in this

matter given his position, he does make a convincing argument for

the limited case of electronic access to text-only databases.

However, his points do not address the larger issues raised in

the OTA intellectual property studies.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Alexander, Adrian W., and Julie S. Alexander. "Intellectual

Property Rights and the 'Sacred Engine': Scholarly Publishing in

the Electronic Age." In Advances in Library Resource Sharing,

ed. Jennifer Cargill and Diane J. Graves, 176-192. Westport,

Conn.: Meckler, 1990.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Adrian and Julie Alexander give a fine overview of the 1986 OTA

report, as well as a conference on intellectual property rights

held in 1987 by the Network Advisory Committee of the Library of

Congress. They conclude with a broad discussion of the potential

for electronic publishing for the scholarly research and

publication process, which echoes many of the themes discussed at

recent meetings of the Coalition for Networked Information.

They maintain, as some CNI speakers have, that electronic

publishing represents an opportunity for universities to

recapture their intellectual property from the expensive and

fruitless cycle of sale back and forth to publishers. They also

point out that publishers want to capture this potential

publication medium as well.

+ Page 168 +

----------------------------------------------------------------

Shuman, Bruce A., and Joseph J. Mika. "Copyrighted Software and

Infringement by Libraries." Library and Archival Security 9, no.

1 (1989): 29-36. (ISSN 0196-0075)

----------------------------------------------------------------

Shuman and Mika provide a good overview of the current state of

software piracy and copyright infringement, with a few additional

comments that describe the situation of libraries which circulate

software. They are quite critical of the practice of

"shrink-wrap" licensing which many vendors have taken up. This

is the familiar tactic of pasting a license agreement with many

restrictions on the outside of a shrink-wrapped software package,

with a statement to the effect of "if you open this package, you

thereby agree to this license." They describe the many problems

involved in trying to police the use of software by library

patrons, and state that: "Librarians will continue to find

themselves between copyright holders and license-vendors, eager

to recover the money they feel entitled to, and patrons (and

sometimes library employees) who wish to 'liberate' programs,

whether out of simple greed, a love of the challenge, altruism,

or a 'Robin Hood' complex."

----------------------------------------------------------------

Denning, Dorothy E. "The United States vs. Craig Neidorf."

Communications of the ACM 34, no. 3 (March 1991): 24-32. (ISSN

0001-0782)

----------------------------------------------------------------

Finally, I would like to conclude this column with an example of

the kinds of troubling legal actions that are surely brewing on

the horizon.

The March 1991 Communications of the ACM was partly devoted to a

debate concerning electronic publishing, constitutional rights,

and hackers. The article by Dorothy Denning was a description of

the trial of Craig Neidorf, a pre-law student at the University

of Missouri. Neidorf was charged by a federal grand jury with

wire fraud, computer fraud, and interstate transportation of

stolen property.

+ Page 169 +

All this because he published a document (containing what turned

out to be public domain information) in an electronic journal he

edited. The electronic journal was called "Phrack," a

contraction of the terms "Phreak" (the act of breaking into

telecommunications systems) and "Hack" (the act of breaking into

computer systems). The document in question concerned the E911

system of Southwestern Bell, and it contained only information

that was already in the public domain. The charges against

Neidorf were dropped when this was brought up during the trial,

but Neidorf was left with all his court costs, amounting to

$100,000.

Now, regardless of what one thinks of Neidorf or the ethics of

hacking, the fact that the U.S. government can bankrupt an

individual (or institution!) by making groundless accusations of

publishing "secret" electronic documents bears attention!

Neidorf's case may potentially mark the beginning of entirely new

types of censorship revolving around electronic media. Denning's

article points out that currently the government can seize all

computer equipment and files of an individual or organization,

and hold them for months. This kind of search and seizure (again

on mistaken grounds) devastated one small company called Steve

Jackson Games. Denning discusses this incident as well, and it

is chilling to imagine happening by accident to one's own

organization.

Problems of copyright and the new digital media are only now

beginning to surface, but they have been inherent in the new

technologies since at least the sixties. Libraries and society

as a whole will increasingly have to face these issues, either in

legislation by a forward-looking congress, or more likely in

painful court trials like the United States vs. Neidorf.

+ Page 170 +

About the Author

Martin Halbert

Automation and Reference Librarian

Fondren Library

Rice University

Houston, TX 77251-1892

HALBERT@RICEVM1.RICE.EDU

----------------------------------------------------------------

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is an electronic

journal. It is sent free of charge to participants of the

Public-Access Computer Systems Forum (PACS-L), a computer

conference on BITNET. To join PACS-L, send an electronic mail

message to LISTSERV@UHUPVM1 that says: SUBSCRIBE PACS-L First

Name Last Name.

This article is Copyright (C) 1991 by Martin Halbert. All Rights

Reserved.

The Public-Access Computer Systems Review is Copyright (C) 1991

by the University Libraries, University of Houston, University

Park. All Rights Reserved.

Copying is permitted for noncommercial use by computer

conferences, individual scholars, and libraries. Libraries are

authorized to add the journal to their collection, in electronic

or printed form, at no charge. This message must appear on all

copied material. All commercial use requires permission.

----------------------------------------------------------------

+ Page 39 +

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Harnad, Stevan. "Post-Gutenberg Galaxy: The Fourth Revolution

in the Means of Production of Knowledge." The Public-Access

Computer Systems Review 2, no. 1 (1991): 39-53.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

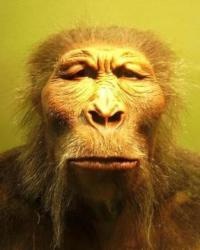

1.0 The Evolution of Human Communication and Cognition

There have been three revolutions in the history of human

thought, and we are on the threshold of a fourth. The first took

place hundreds of thousands of years ago when language first

emerged in hominid evolution and the members of our species

became inclined--in response to some adaptive pressures whose

nature is still just the subject of vague conjecture [1]--to

trade amongst themselves in propositions that had truth value.

There is no question but that this change was revolutionary,

because we thereby became the first--and so far the only--species

able and willing to describe and explain the world we live in.

It remains a mystery--to me at any rate--why our anthropoid

cousins, the apes, who certainly seem smart enough, do not share

this inclination of ours. At any rate, this divergence between

our two respective species was a milestone in human communication

and cognition, making it possible for culture to develop and be

passed on by oral tradition.

That momentous adaptation seems to have had a neurological basis.

Injuries to certain areas of the left side of the

brain--Wernicke's area and Broca's area, to be exact--result in

language-specific deficits in speaking and understanding [2, 3].

So whatever the evolutionary changes underlying language were,

they were imprinted as permanent modifications of our neural

hardware.

The second cognitive revolution was the advent of writing, tens

of thousands of years ago. Spoken language had already allowed

the oral codification of thought; written language now made it

possible to preserve the code independent of any speaker/hearer.

It became, if you like, an implementation-independent code. No

one knows for sure whether there was any corresponding change in

our cerebral hardware. There is nominally a region in the left

frontal lobe--Exner's area--that is dubbed the "writing center,"

and there are certainly specific neurological problems associated

with "dyslexia" or reading disorder. But all of this neurology

is complicated and ill-understood, and no "pure" alexia

(inability to read), without any other associated visual or motor

problems, has been found. So it is more likely, I think, that

writing and reading were cognitive and motor skills that we

acquired without any organic evolutionary change in our brains;

they were merely learned adaptations of the same hardware we had

all along.

+ Page 40 +

No precise starting point can be assigned to either science or

literature. The former began with the first true proposition

about the world and the latter either with the first such true

proposition that was also formulated elegantly, or perhaps with

the first untrue proposition. In either case, the oral tradition

was already equipped to produce both science and literature,

although perhaps science, being a little too constrained by the

limits of memory and accuracy in the word-of-mouth medium, was

the greater beneficiary of the advent of writing, with the

incomparably greater reliability and systematization it conferred

in preserving the words, and hence the thoughts, of others.

But there were constraints on writing too. For whereas spoken

language conformed well to both the transmitting and receiving

powers of human thinkers (perhaps as a reflection of its specific

dedicated neurology), writing was somewhat out of synch with

thought. It was slow. And worse than that, it had a much more

limited scope, for whereas a spoken proposition could be heard by

several people, even by multitudes, a written one could only be

read by one at a time. This could be done serially by limitless

numbers of readers, of course, and this was the real strength of

writing, but it was purchased at the price of becoming a much

less interactive medium of communication than speech. The form

and style of written discourse accordingly adapted to this

lapidary new medium--again, not neurologically, but consciously

and by convention--constraining the writer to be more precise in

some respects, but also allowing him more freedom to redraft and

reformulate his text in composing it. In becoming less

interactive, writing also became less spontaneous than speech,

more deliberate, and more systematic. One might also say it

became less social and more solipsistic, although its ultimate

social reach became much larger, limited only by the slow pace of

copyists in providing the text to disseminate.

The third revolution took place in our own millennium. With the

invention of moveable type and the printing press, the laborious

hand-copying of texts became obsolete, and both the tempo and the

scope of the written word increased enormously. Texts could be

distributed so much more quickly and widely that again the style

of communication underwent qualitative changes. If the

transition from the oral tradition to the written word made

communication more reflective and solitary than direct speech,

print restored an interactive element, at least among scholars,

and, if the scholarly "periodical" was not born with the advent

of printing, it certainly came into its own. Scholarship could

now be the collective, cumulative, and interactive enterprise it

had always been destined to be. Evolution had given us the

cognitive wherewithal and technology had given us the vehicle.

+ Page 41 +

Of course, there had already been a prominent exception to the

impersonal trend set in motion by writing, namely, private

letters. These made it possible for people to communicate even

when they were separated by great distances, although again the

pace of the communication was much slower and less interactive

than live conversation, and it continued to be so, even after the

advent of print.

Many minor and major technological changes followed, but none, I

think, qualify as revolutionary. The means of transportation

improved, so the written word could be circulated more quickly

and more widely. The typewriter (and eventually the word

processor) made it much easier to generate and modify one's

texts. Photocopying made it possible to duplicate, and desktop

publishing to print, even texts that weren't worth duplicating

and printing. And the telephone all but did in the art of letter

writing altogether, probably because it restored the natural

tempo of spoken communication to which the brain is

constitutionally adapted. Of course, phoning had the

disadvantage of not leaving a permanent record, but for that

there were tape recorders, and so on.

The reason I single out as revolutionary only speech, writing,

and print in this panorama of media transformations that shaped

how we communicate is that I think only those three had a

qualitative effect on how we think. In a nutshell, speech made

it possible to make propositions, hand-writing made it possible

to preserve them speaker-independently, and print made it

possible to preserve them hand-writer-independently. All three

had a dramatic effect on how we thought as well as on how we

expressed our thoughts, so arguably they had an equally dramatic

effect on what we thought. The rest of the technological

developments were only quantitative refinements of the media

created by speech, writing, and print. The purist might, with

some justification, even hold that print was just a quantitative

refinement of writing, but let's argue about that another time:

the historic evidence for the impact of print is considerable.

+ Page 42 +

The two factors mediating the qualitative effects were speed and

scale. Speech slowed thought down, but to a rate for which the

brain made specific organic adaptations. Our average speaking

rate is a biological parameter; it is a natural tempo.

Hand-writing slowed it down still further, but here the

adaptations were strategic and stylistic rather than

neurological. In writing, the brain was underutilized. Evidence

for this comes from the fact that when the typewriter and the

word processor allowed the pace of writing to pick up again, we

were quite ready to return to a tempo closer to our natural one

for speech. On the other hand, the constraints of the written

medium are substantive, and they affect both form and content, as

anyone who has tried to use raw transcripts of spontaneous speech

can attest. What is acceptable and understandable in spoken form

is unlikely to be acceptable and understandable in written form,

and vice versa.

In a sense, there are only three communication media as far as

our brains are concerned: the nonverbal medium in which we push,

pull, mime and gesticulate [4]; and two verbal media--the natural

one, consisting of oral speech (and perhaps sign language), and

the unnatural one, consisting of written speech. Two features

conspire to make writing unnatural. One is the constraint it

puts on the speed with which it allows thoughts to be expressed

(and hence also on the speed with which they can be formulated),

and the other is the constraint it puts on the interaction of

speaking thinkers--and hence again on the tempo of their

interdigitating thoughts, both collaborative and competitive.

Oral speech not only matches the natural speed of thought more

closely, it also conforms to the natural tempo of interpersonal

discourse. In comparison, written dialogue has always been

hopelessly slow: the difference between "real-time" dialogue and

off-line correspondence. Hopeless, that is, until the fourth

cognitive revolution, which is just about to take place with the

advent of "electronic skywriting."

+ Page 43 +

2.0 Scholarly Skywriting: A Personal Glimpse of the Potential

Panorama

I must now turn from impressionistic history to personal

anecdote. My own skyward odyssey in the newest communication

medium, the airwaves of electronic telecommunication networks,

had its roots in a long-standing personal penchant for scholarly

letter-writing (to the point of once being cited in print as

"personal communication, pp. 14-20"). These days few share my

epistolary bent, which is dismissed as a doomed anachronism.

Scholars don't have the time. Inquiry is racing forward much too

rapidly for such genteel dawdling--forward toward, among other

things, due credit in print for one's every minute effort. So I

too had to resign myself to the slower turnaround but surer

rewards of conventional scholarly publication. In fact, a decade

and a half ago I founded a scholarly journal in the conventional

print medium, though Behavioral & Brain Sciences (BBS) is hardly

a conventional journal.

2.1 Behavioral and Brain Sciences

Modelled on Current Anthropology (CA, which was founded by the

anthropologist Sol Tax, who in turn modelled it on the extreme

participatory democratic practices of the native North American

peoples he studied), BBS's unique feature is "creative

disagreement" [5]. Specializing in important and influential

ideas and findings in the biobehavioral sciences, BBS, after a

round of particularly rigorous peer review (involving five to

eight referees representing the multiple areas that candidate

manuscripts must impinge upon), offers to the authors of accepted

papers the service of "open peer commentary." Their manuscript

is circulated to specialists across disciplines and around the

world, each invited to submit 1,000-word commentaries that

discuss, criticize, amplify, and supplement the work reported in

the target article, which is then published along with the

commentaries (often twenty or more

) and the author's formal

response to them [6]. BBS's open peer commentary service has

evidently been found valuable by the world biobehavioral science

community, because already in its fourth year its "impact factor"

(citation ratio) had become one of the highest in its field [7,

8].

+ Page 44 +

2.2 Limitations of Print Journals

Like other print journals, BBS is prisoner to the temporal,

geographic, and (shall we call them) "internoetic" constraints of

the conventional paper publication medium. In that medium, new

ideas and findings are written up and then submitted for peer

review [9, 10]. The refereeing may take anywhere from three

weeks to three months. Then the author revises in response to

the peer evaluation and recommendations, and when the article is

finally accepted, it again takes from three to nine months or

more before the published version appears (perhaps earlier, when

circulated informally in preprint form). That's not the end of

the wait, however, but merely the beginning, for now the author

must wait until his peers actually read and respond in some way

to his work, incorporating it into their theory, doing further

experiments, or otherwise exploring the ramifications of his

contribution. After all, that's why creative scholars publish--

not to put another line on their resumes, but to collaborate with

their peers in expanding our collective body of knowledge.

It usually takes several years, however, before the literature

responds to an author's contribution (if it responds at all) and

by that time the author, more likely than not, is thinking about

something else. So a potentially vital spiral of peer

interactions, had it taken place in "real" cognitive time, never

materializes, and countless ideas are instead doomed to remain

stillborn. The culprit is again the factor of tempo: the fact

that the written medium is hopelessly out of synch with the

thinking mechanism and the organic potential it would have for

rapid interaction if only there were a medium that could support

the requisite rounds of feedback, in tempo giusto!

Hopeless, as noted earlier, until the forthcoming fourth

cognitive revolution makes it possible to restore scholarly

communication to a tempo much closer to the brain's natural

potential while still retaining the rigor, discipline, and

permanence of the refereed written medium.

+ Page 45 +

2.3 Discussion Groups on the Net

I will try to illustrate with an account of my own first

(unrefereed) glimpse of the Platonic world of scholarly

skywriting. Most of the world's universities and research

institutions are linked together by various international

electronic networks such as BITNET and Internet (called,

collectively, the "Net"). Electronic mail ("e-mail") can be sent

via the Net, usually within minutes, to London, Budapest, Tel

Aviv, Tokyo, lately even Minsk. But the feature that has the

most remarkable potential is multiple reciprocal e-mail:

electronic discussion groups in which every message is

immediately disseminated to all members.

These groups first formed themselves anarchically, on various

networks, the biggest of them called USENET, and were devoted

partly to technical discussion about computers and information,

the technologies that had built the Net, and otherwise to

"flaming": free-for-all back and forth messages by anyone, on any

topic under the sun. Next, discussion groups devoted to specific

topics (e.g., computers, politics, language, culture, and sex)

began to form, and these in turn split into "unmoderated" and

"moderated" groups. Anyone with an e-mail address whose

institution was connected to USENET could post to an unmoderated

group, and the message would automatically be sent to everyone

who was "subscribed" to the group.

It was because most of the unmoderated groups were quite chaotic

that the moderated groups were formed. In these, all submissions

had to be channeled through a "moderator," but this was usually

someone with no special qualifications or expertise, so the

quality of the information on the moderated groups was still very

uneven, and, with a few exceptions (principally technical

discussions about computing itself), these groups were mostly

havens for uninformed students and dilettantes rather than

respectable scholarly forums for learned specialists in the

subject matter under discussion, a subject matter that by now

ranged across the humanities, the social sciences, and the

natural sciences.

+ Page 46 +

This was the status quo on the Net--a communication medium with

revolutionary intellectual potential being used mostly as a

global graffiti board (in all fields other than computing

itself)--when I first sampled the skyways several years ago in a

large (unmoderated) USENET group called "comp.ai" (devoted to the

topic of artificial intelligence, a subfield of my own specialty,

cognitive science). I had heard that there was a lot of ongoing

discussion on comp.ai about something that had appeared in

BBS--Searle's "Chinese Room Argument" [11]. The content of that

discussion is not relevant here. Suffice it to say that about a

profound and complex topic a great deal of nonsense was being

posted on comp.ai by people who knew very little (mostly students

and computer programmers). This initial demography, and the

unscholarly level of discussion that prevailed because of it, was

and still is one of the principal obstacles to the Net's

realizing its real potential. For what true scholar would

condescend to join these innocents in serious scholarly

discussion, and in such an anarchic medium!

Well, draw your own conclusions, but that did not stop me.

Whether it was my partiality for letter-writing or for creative

disagreement, I decided to test out the airways, but consciously

applying self-imposed constraints, since the medium would not

provide them for me. My postings to comp.ai would be

conscientiously thought out and carefully written, as if they

were for a serious refereed journal, with a sophisticated

scholarly readership--for posterity, in fact. Hardest of all, I

would treat the contributions of my interlocutors as if they had

been serious and scholarly ones too, and when these were

uninformed or in error, I would endeavor to correct them in a

dignified and respectful way that would be informative and

instructive to all, solemnly trying to correct the Nth instance

of the same egregious mistake with a Nth new aspect or dimension

of the problem under discussion, always with the objective of

advancing the ideas for all skygazers. Indeed, critical to my

efforts at sobriety and self-discipline was maintaining for

myself a conscious fantasy that, silent among the thousands of

eyes trained skyward, were my peers, and not just the rookies I

was jousting with.

+ Page 47 +

Lest it be thought that this was all just some sort of altruistic

exhibition, however, let me hasten to report that I found myself

by far the greatest beneficiary of this exercise. For the

remarkable fact is that even under these primitive demographic

conditions my own ideas profited enormously from the skywriting

interactions. The problem under discussion (and it only became

evident to me during the discussion just what that problem was) I

dubbed, in the course of the skywriting, "the symbol grounding

problem," and it has since generated not only a series of (alas,

conventional, ground-based) papers [12, 13, 14], but also a

cottage industry in the form of a theme for workshops and

symposia [15], and soon, no doubt, dissertations. All this as a

consequence of aerobatics with mere rookies. "So what would it

have been like," I then asked myself, "if the best minds in the

field were on the Net, skywriting away with the rest of us?"

2.4 Psycoloquy

When I founded BBS fifteen years ago, I had been inspired by the

remarkable potential of "open peer commentary" as revealed

through an article by Gordon Hewes [16] in Sol Tax's commentary

journal, CA. That article was on the origin of language, a topic

that had been under an informal moratorium (as breeding only idle

conjectures) imposed by the Paris Societe Linguistique a century

earlier. Hewes and his animated commentators across disciplines

so piqued my own interest in the topic that I: (1) co-organized

an international conference under the auspices of the New York

Academy of Sciences [17] (a conference that effectively put an

end to the moratorium on the topic and went on to spawn an

uninhibited series of language-origins conferences, e.g.,

Raffler-Engel et al. [18]); and (2) I founded BBS, convinced that

Sol Tax's "CA Comment" principle could be generalized beyond its

discipline of origin.

A decade and half later my own rewarding experience with

electronic skywriting has convinced me that this newest medium's

unique potential to support and sustain open peer commentary must

now be made generally available too, so I have founded