Riddler of the Sands: Profile of Graham Hancock

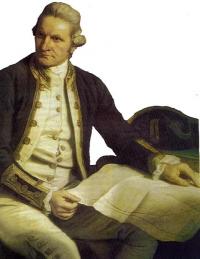

It was back in 1983 that Graham Hancock, author of the multi-million-selling book Fingerprints of the Gods, experienced a revelation that would change his life. At the time a humble freelancer for the Economist in east Africa, he heard mention of a myth which claimed that the Ark of the Covenant had for many centuries been guarded by a secret sect of monks in Ethiopia. Then, one day, he came across a dark, windowless room partially illuminated along one wall by a fantastic flickering image. Here, he realised, was a magical glimpse of the future, and its name was Raiders of the Lost Ark.It is misleading to say that since that cinematic epiphany, Hancock has never looked back – not least because he has done little else but delve into the past. But in turning his focus to the mysteries of the ancient world, and popularising them with a mixture of amateur enthusiasm and slick exaggeration, he has transformed himself into a hugely successful author and, now, a promising TV personality. With the three-part series Quest for the Lost Civilisation that he has written and presented for Channel 4, he is set to become the New Age answer to David Attenborough.

The legitimacy that a TV series confers, however, is also accompanied by greater scrutiny. Questions have been asked about the bona fides of the man they call the 'Indiana Jones of alternative archaeology'. Many critics identify Hancock as part of a worrying cultural trend towards 'occult fantasies'.

By his own admission, Hancock's highest academic achievement is a sociology degree from Durham University. He cheerfully confirms that he is "awful" at maths and astronomy – "I took my maths O-level six times" – and that he "can't read a word of hieroglyphs"; yet he has drawn on astronomy, mathematical calculation and Egyptology, among many other disciplines, to propagate his theory that an advanced civilisation thrived and was destroyed some 7,000 years before the first pyramids in Egypt were built. To say that this argument is not currently circulating in the mainstream of historic debate is rather like pointing out that at the moment there are no great white sharks in Regent's Park boating lake.

Although he concedes that he would dearly like to be proved right, he says he is unbothered by the disdain with which his hypothesis has been greeted in academia. "There are serious problems in Egyptology," he says, "even if we are all completely wrong."

By "we", Hancock means he and his fellow 'para-scientists', the collection of popular writers who have closed the gap between well-researched science and plausible science fiction. The originator of this particular genre was the Swiss hotelier, Eric Von Daniken, who in 1968 wrote Chariots of the Gods, in which he suggested civilisation was kick-started on earth by a band of visiting aliens. The book was demonstrable nonsense and, naturally, sold millions worldwide.

While critical of Daniken's methods, Hancock acknowledges his debt to the former barman. He named his own book Fingerprints of the Gods in recognition of Daniken's marketing nous. It was a wise move. Since its publication three years ago, Fingerprints has sold 3,500,000 copies and been translated into 20 languages.

It's a far more solid work than Daniken's. Hancock uses a gradual accumulation of selective research, strange coincidences, provocative theories and baffling science to draw the reader into an almost mystical sense of wonder. It's testament to Hancock's abilities as a writer that it's easy to forget he does not come up with one shred of irrefutable evidence to support his case. Still, in an era where the very concept of objective truth is almost laughably out of fashion, this is not necessarily a problem.

Indeed, to cash-in effectively on the X-Files audience, it's much better if the mystery remains unsolved. That way you can claim, as Hancock does, that enigmatic ancients (gods/ETs/advanced beings) have passed on a crucial message encoded in buildings around the world – the pyramids in Mexico and Egypt, the Angkor Wat temple in Cambodia, the Easter Island statues – that, if deciphered, may well lead us to spiritual salvation and protect us from imminent physical destruction. Of course, the specialists are too myopic to see the bigger picture, so it falls to 'generalists' such as Hancock to grapple with a cosmic riddle so profound that it can't possibly be addressed in just one book.

Heaven's Mirror, which accompanies the TV series, is the fifth work Hancock has published on ancient mysteries. The first was The Sign and the Seal, his Steven Spielberg-inspired investigation into the lost Ark. Unlike in the film, the sacred relic was not retrieved, but we did learn that the succession of monks who supposedly looked after it were destined to die of cancer, one by one.

In The Mars Mystery, his fourth book, he warned that Earth could be destroyed by an asteroid within 30 years and that the Cydonia shapes visible on Mars were probably artificial structures. Dr Andrew Coates of Mullard Space Laboratory says the chances of earth being hit by cataclysmic meteorite in that time frame are "less than winning the lottery". Furthermore, Mars Global Surveyor has confirmed that Cydonia was nothing more than "tricks of the light".

It would be a mistake, though, to conclude that Hancock is a cynical charlatan. He appears to be genuinely consumed by his research – a fact that makes his TV performance disturbingly credible. "It's completely changed my life," he says, "and I don't mean in a material sense. There is a spiritual key here."

Born in 1950 in Edinburgh and brought up in the Church of Scotland, Hancock quickly rejected Christianity. His father was a military doctor who took the family around the world. Hancock had two siblings who died as children in India of illnesses that he says could have been treated in Britain. The family then settled in Durham.

As a young man, he drifted into a series of jobs before landing an editorial position in the late Seventies at the New Internationalist. A colleague from that period remembers him as someone "caught up in the travails of his own life. He was a one-man-band crusader, not constrained by the collective spirit of the magazine. I have problems with organisations," says Hancock. "There's always somebody I don't get on with. It drains my energy and I don't like it."

His first wife was a Somali and it was to Africa that he headed, initially on a research grant, and then as a stringer for various newspapers and magazines. He failed to make a big impact and after a while set up his own publishing and PR business which did work for some questionable governments. "There is something very seductive about power," he now says, deeply regretting his involvement with individuals such as the dictator Siad Barré . "They were terrible men who'd kill you for anything. I never really thought about that. I think I was a profoundly amoral individual. I had a bad name."

A fellow reporter thinks that Hancock is too harsh on himself. "He was gentle, reflective and self-deprecating, quite unlike the other macho hacks, but a bit slow on his feet. He was young and naive, that's all." Either way, Hancock, in his search for spiritual enlightenment, is keen to set the record straight. "I think it's terribly important that your actions harmonise with your words," he says. "When I look back on my life, I see a lot of hypocrisy." It was his third wife, the photographer Santha Faiia, a Malaysian Tamil, who advised him to change his business partners. They now own houses in Devon and London and travel four months of the year, but they were nearly bankrupt before Fingerprints took off.

He wrote a number of well-received, but unbought books, in the straightforward journalistic tradition, including a critique of aid and charity, Lords of Poverty, and Aids: The Deadly Epidemic. His company eventually collapsed but not before he learned the ins and outs of packaging information. As he now puts it: "I know how to manufacture books."

Having found slim pickings on conventional investigative territory, he moved to the highly profitable margins. With TV deals, Hancock's earning power is now, like the ancient learning he ascribes to the Mayans and Egyptians, astronomical. Experts who have spent their lives diligently working away in poorly paid obscurity, look upon Hancock's exposure with no little bitterness. "Egyptologists do find us threatening," he says with painful understatement. "They find it annoying that we sell a lot of books."

A few years ago, the respected Egyptologist, Jaromir Malak, lamented in a review of Fingertips of the Gods, the fact that populists like Hancock were given an "easy unopposed ride" in the media because experts failed to refute their claims. It's as if archaeologists who have spent years digging in the desert don't want to dirty their hands by entering a debate with the likes of Hancock. Malak was reluctant to speak when contacted.

The responsibility, however, now rests with the men and women of science to make their case known in an accessible and compelling fashion. "There is a rebellion against orthodox thinking," says Hancock, and he has a point. The public has lost interest, and it's too easy to blame the media. "On one level, you can say the whole thing is nonsense," he says, "but on another, it's quite powerful. You're forced to suspend disbelief."

The insular world of ancient history is struggling nowadays to capture the public imagination. Hancock's methodology may be suspect but his presentational skills can't faulted. If traditional historians are interested in making the pyramids relevant to new generations, they would do well to learn from the sociology graduate. Otherwise, it will be the origins of our own civilisation, rather than one that almost certainly never existed, that we will lose.

The following claims are often made for pyramids. All are unproven scientifically:

- Study of the Great Pyramid at Giza has shown that the ancient Egyptians were able to calculate the weight and circumference of the earth and its distance from the sun.

- The three pyramids at Giza are said to be laid out in the same alignment as part of the constellation Orion, with the Milky Way represented by the Nile.

- If the dimensions of the Great Pyramid are substituted with years, the chambers and passageways of the building become a calendar of prophecy, predicting world events through the ages such as the birth of Jesus Christ and the Second World War.

- The Great Pyramid lies at the centre of gravity of the continents, and in the centre of all of the land area in the world.

- The Great Pyramid shows that the Egyptians knew and used the number pi, the discovery of which was previously attributed to the Greeks.

- The pyramid shape is believed to hold special powers, channelling various types of energy from magnetic to cosmic. These energies are said to calm inner turmoil, aid sleep, improve the taste of wine, cigarettes and fruit juice, and keep razor blades sharp...